When I think about transportation projects, I remember Kate Keller rounding up approximately a million human-powered wheeled vehicles, so we could try them and compare them and consider the relationship between function and design.

When I think about transportation projects, I remember Kate Keller rounding up approximately a million human-powered wheeled vehicles, so we could try them and compare them and consider the relationship between function and design.

Transportation involves the movement of people or goods, so these small human-powered examples count, even when powered by very small humans. (See below.)

Why do wheels help so much, when we need to move things (or ourselves)? What design modifications help a wheel work well? What about handles? What about the way the weight of the goods is balanced?

Kids had time to think about all these questions as they were actively trying out several vehicles at each station, comparing wheelbarrows and garden carts, or several kinds of strollers, dollies for working under cars, wheeled suitcases, even wheeled desk chairs. Then they had time to think about what they were noticing, and add to their notes or charts, before rotating to their next station.

In this activity, unlike some projects time set-ups, everybody tried everything. We would not have been forgiven by the people who didn’t get to try the scooter. Also, we wanted to avoid any suggestion of girl stuff and boy stuff.

When I think of transportation projects, I’m bound to think of this photograph of Troy, experiencing the enhanced mobility provided by his very first car, in the form of a paper plate. We added cars in the third round of a simulation of the relationship between transportation and trade, usually referred to as “the villages.” A Touchstone alum turned transportation planner (my son, Colby Brown) heard that we’d gotten a grant to develop curriculum about transportation. He said, “You have to do this Touchstone style. You have to model the interactions with a simulation on the playground.”

We added cars in the third round of a simulation of the relationship between transportation and trade, usually referred to as “the villages.” A Touchstone alum turned transportation planner (my son, Colby Brown) heard that we’d gotten a grant to develop curriculum about transportation. He said, “You have to do this Touchstone style. You have to model the interactions with a simulation on the playground.”

So Kate Keller, resident genius at translating complex concepts into compelling experience, designed a simulation in which students pretended to live and survive the seasons in three villages, widely spaced on our school grounds–under the gazebo out front, at the back of the rear playing field, and at the bottom of the slide.

So Kate Keller, resident genius at translating complex concepts into compelling experience, designed a simulation in which students pretended to live and survive the seasons in three villages, widely spaced on our school grounds–under the gazebo out front, at the back of the rear playing field, and at the bottom of the slide.

Kate put special care into making sure that none of the villages could be seen from the others, so transportation was also the only route for communication, true to most of human history. In order to conduct a trade, the traders had to travel.

We imagined each village having its own geography–mountains, woods, or a lake in the form of the playing field, which students pretended to cross by pulling saucer-sled boats.

Each geography had its own resources to offer in trade, for example cattails from the lakeside, wood from the forests, or cloth woven from the wool of mountain-tolerant sheep. At first, the villagers had nothing but their own bodies to carry their goods, but in the second round each group had some additional transportation, such as a wheelbarrow.

had nothing but their own bodies to carry their goods, but in the second round each group had some additional transportation, such as a wheelbarrow.

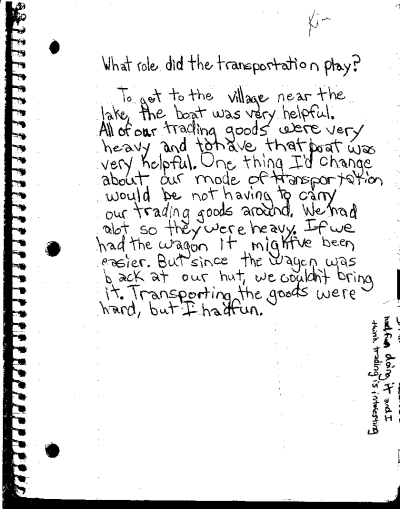

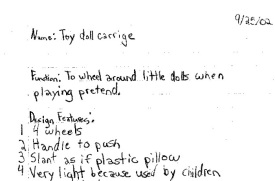

Here’s one student’s writing, evaluating how that day’s experience had worked:

I kept the little note at the side, saying that trading was interesting, because that was such an understatement. The students were wildly excited about trading. In one debriefing conversation, a student said, “It’s hard to take part in the simulation and learn as an observer at the same time, because I get so excited about the trading.”

I kept the little note at the side, saying that trading was interesting, because that was such an understatement. The students were wildly excited about trading. In one debriefing conversation, a student said, “It’s hard to take part in the simulation and learn as an observer at the same time, because I get so excited about the trading.”

Looking back, I appreciate more than ever the engagement and thoughtfulness, the serious playfulness at its best, that gave rise to such astute observations about what we were asking students to do. I appreciate also the ways students supported each other in being both participants and researchers, reminding each other of our questions: What impact did the transportation have on the trading? What impact did the need for trade have on the need for transportation?

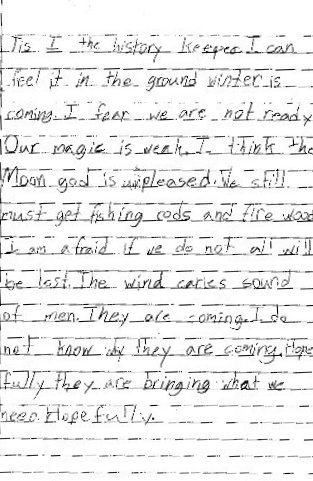

Village culture evolved very quickly, so magic stones and medicinal pieces of bark were also traded, and one student, writing up the day’s events, wrote as the History Keeper

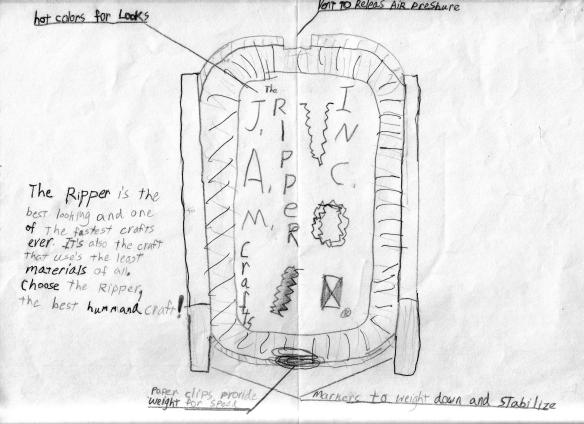

In the third round, after class discussion about where to take our simulation next, we introduced transportation that involved motors–individual private cars, a toll bridge, and a train route in the tunnel through the mountain of the school. As it played out, students were surprised at the expense of private transportation, at least in this simulation. In one of the replays of the curriculum in later years, a student yelled in exasperation, “This car is making me go broke!”

In the third round, after class discussion about where to take our simulation next, we introduced transportation that involved motors–individual private cars, a toll bridge, and a train route in the tunnel through the mountain of the school. As it played out, students were surprised at the expense of private transportation, at least in this simulation. In one of the replays of the curriculum in later years, a student yelled in exasperation, “This car is making me go broke!”

It’s torture to leave out everything I’m having to leave out. I want to describe just one more of our transportation projects. Later in the unit, we split into groups working parallel and reporting to each other–about transportation access issues, or about what it’s like to make a transportation plan. For example, one group designed a bike path from West Upton village to our school.

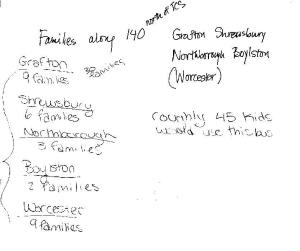

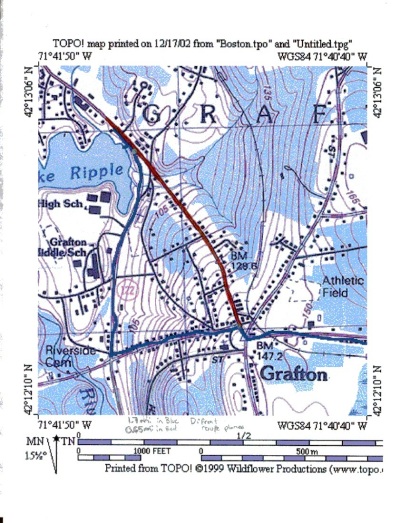

Another planned several bus routes. No bus could pick up all our students, from the many towns in which they lived. But when we had mapped all our own class member locations, at the beginning of the year, Kate and I had noticed how many families lived near the state highway very close to the school. The bus route planning group spent a lot of time with maps on which they located all the school families involved in the clustering we had noticed. They made two lists, the one I’ve shown, and another of families who lived south and east of the school, in Milford and Hopkinton. Then they designed routes.

Another planned several bus routes. No bus could pick up all our students, from the many towns in which they lived. But when we had mapped all our own class member locations, at the beginning of the year, Kate and I had noticed how many families lived near the state highway very close to the school. The bus route planning group spent a lot of time with maps on which they located all the school families involved in the clustering we had noticed. They made two lists, the one I’ve shown, and another of families who lived south and east of the school, in Milford and Hopkinton. Then they designed routes.

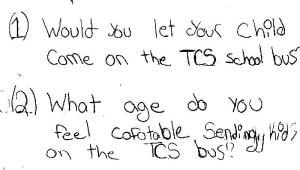

One of the students pointed out that parents might or might not be willing to let their children ride a bus, even a school-sponsored bus. She might have heard about the parent-organized bus to Worcester that ran for a few years, with continual difficulties around poor communication. So she designed the questionnaire to the right.

One of the students pointed out that parents might or might not be willing to let their children ride a bus, even a school-sponsored bus. She might have heard about the parent-organized bus to Worcester that ran for a few years, with continual difficulties around poor communication. So she designed the questionnaire to the right.

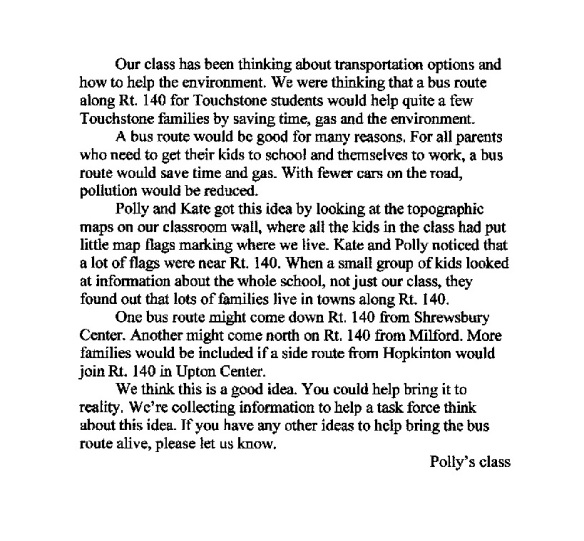

The bus route planning group had several final products to share, including maps made on Topo software, annotated with the proposed routes, and an article which ran in the school newsletter.

The bus route planning group had several final products to share, including maps made on Topo software, annotated with the proposed routes, and an article which ran in the school newsletter.

Although the bus routes never did materialize, those Very Young Transportation Demand Forecasters had learned lessons almost impossible with anything less connected to their own experience.

That was true, of course, of the whole deal. In the next post I want to write about the transportation field trips, giant projects time sessions on many kinds of wheels.

Two extra notes:

#1 This post is the third in a series. The first post in this series about Projects Time describes some logistics, considers the social benefits of this format for hands-on inquiry, and takes a flyover of a typical afternoon of outdoor projects. The second compares accountability and responsibility in the context of Projects Time.

#2 Our hands-on explorations of the physics, history, public policy issues and fun of getting from here to there were the Projects Time side of a curriculum called Transportation Choices, which Kate Keller and I developed with the help of funds from the U.S. Dept of Transportation, administered by the University Transportation Center at Assumption College in Worcester.

One of several university transportation centers throughout the country, the Assumption center focused specifically on K-12 learning about transportation and the environment. When the center closed, its website documentation of the various curricula developed by grantees disappeared from public view–but I’ve saved most of what Kate and I produced to record and evaluate our own work, including curriculum plans and maps and a bibliography. I was able to return to that material and use it in subsequent explorations of the transportation theme.

I’ve written elsewhere about Kate Keller’s gift for developing hands-on developmentally-appropriate activities about complicated ideas. You can find more here.

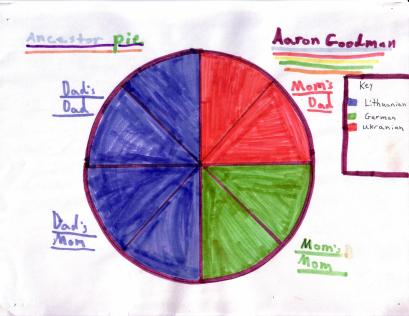

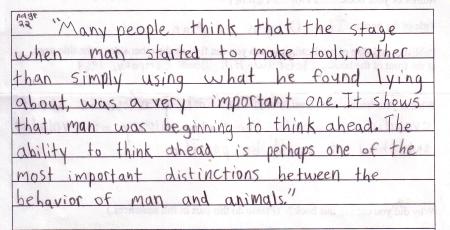

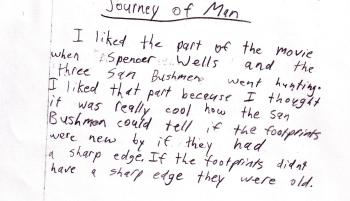

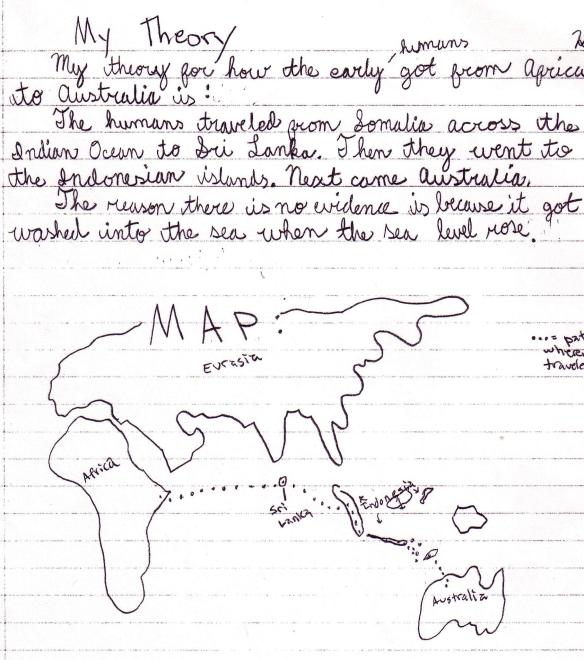

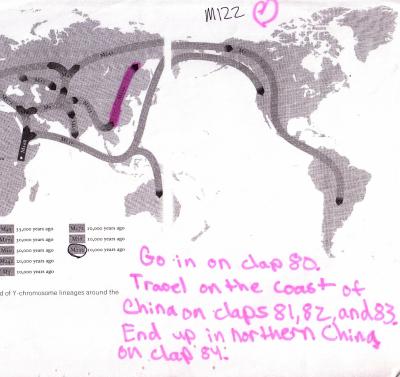

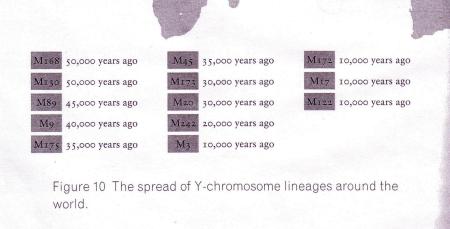

I had offered genetics as a possible book topic, knowing that we’d be doing a side-trip into some learning about genes. We needed that to help us understand the role of Y chromosome genetics in the book by Spencer Wells from which we had borrowed our thematic study’s name, The Journey of Man. One student read Why Are People Different? from Usborne Publishing, and copied a fascinating passage.

I had offered genetics as a possible book topic, knowing that we’d be doing a side-trip into some learning about genes. We needed that to help us understand the role of Y chromosome genetics in the book by Spencer Wells from which we had borrowed our thematic study’s name, The Journey of Man. One student read Why Are People Different? from Usborne Publishing, and copied a fascinating passage.

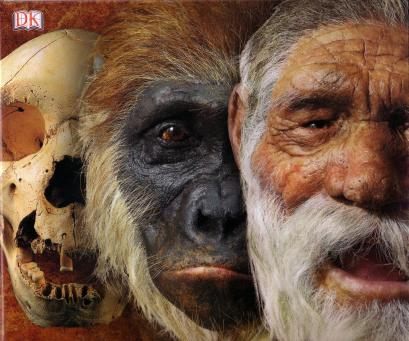

mily found a beautiful picture book about evolution, Our Family Tree: an Evolution Story by Lisa Westberg Peters. It’s become one of my favorite nonfiction books for people of any age,

mily found a beautiful picture book about evolution, Our Family Tree: an Evolution Story by Lisa Westberg Peters. It’s become one of my favorite nonfiction books for people of any age,

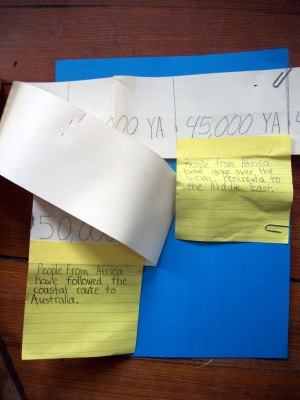

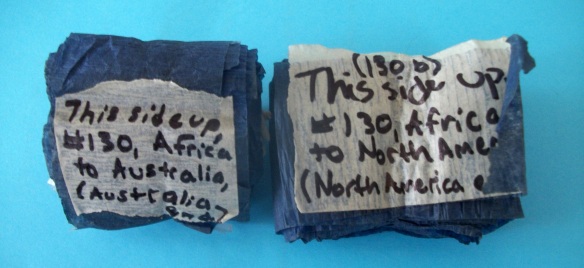

This whole field of human population genetics is moving fast. M130 is now designated as C-M130, and on Wikipedia you can find an excellent, very technical article about the C-M130 lineage, or haplogroup. I love the labels on these streamers, made by students, full of pride in their own technical knowledge at that point.

This whole field of human population genetics is moving fast. M130 is now designated as C-M130, and on Wikipedia you can find an excellent, very technical article about the C-M130 lineage, or haplogroup. I love the labels on these streamers, made by students, full of pride in their own technical knowledge at that point. I’m not sure about this streamer with its many colors, mutation group leading to subgroup, leading to further subgroup, but I think it has the earliest journey on the outside: out of Africa leading to the Middle East, to south central Asia, to central Asia, to Siberia.

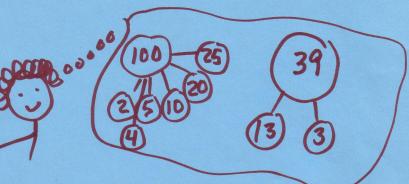

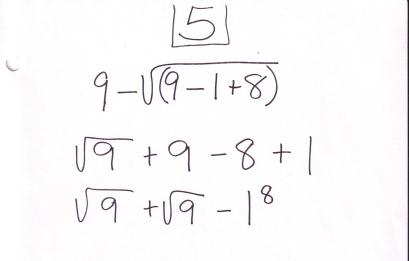

I’m not sure about this streamer with its many colors, mutation group leading to subgroup, leading to further subgroup, but I think it has the earliest journey on the outside: out of Africa leading to the Middle East, to south central Asia, to central Asia, to Siberia. In order to make maps or scaled blueprints, we model large quantities of space by using smaller quantities of space. We let an inch equal a mile, or a centimeter equal a kilometer, or three, or a thousand. Here’s a very basic example from

In order to make maps or scaled blueprints, we model large quantities of space by using smaller quantities of space. We let an inch equal a mile, or a centimeter equal a kilometer, or three, or a thousand. Here’s a very basic example from