This post is the second in a series about Projects Time. Here’s a link to the first.

Unless people saw it in action, Projects Time could be hard to explain.

Colleagues at my own school understood, pretty much. They had given my students years of similar experience in younger classes, that helped them be ready to make longer-term choices, and choose on the basis of activity more than work-partner. They sent me students proficient in physical problem solving , making things work and getting a kick out of the effort. They sent me students with their natural curiosity and creativity still very much intact, full of the energy and momentum for inquiry. (Museum teachers–here at the Tsongas Center in Lowell–always marveled at the hands-on cleverness and persistence of our students.)

, making things work and getting a kick out of the effort. They sent me students with their natural curiosity and creativity still very much intact, full of the energy and momentum for inquiry. (Museum teachers–here at the Tsongas Center in Lowell–always marveled at the hands-on cleverness and persistence of our students.)

My colleagues also sent me students who knew a lot about working with each other. By the time they reached me, most students already knew how to exercise individual creativity in the service of a group effort—contributing ideas, but not needing to have them adopted by the group every time, and increasingly able to listen to each other.

In Projects Time, kids could show leadership in many ways. For one thing, they could help to support collaborative working skills for their classmates who needed more time to develop that particular skill set. (After all, nobody has an aptitude for everything.) Year after year, I could count on finding at least one child who would be especially helpful to students brand new to the school–who didn’t know everybody yet, of course, and typically had had fewer opportunities to practice both group skills and hands-on problem-solving.

In Projects Time, kids could show leadership in many ways. For one thing, they could help to support collaborative working skills for their classmates who needed more time to develop that particular skill set. (After all, nobody has an aptitude for everything.) Year after year, I could count on finding at least one child who would be especially helpful to students brand new to the school–who didn’t know everybody yet, of course, and typically had had fewer opportunities to practice both group skills and hands-on problem-solving.

I loved watching what could happen with minimal adult intervention. I could exercise my care mostly in the background, choosing the groups at the beginning of the year with particular mindfulness, providing appropriately-leveled background reading, giving the most inexperienced students the comfort of a group of two.

In these small interventions, I followed the example of the colleagues from whom I had learned how to teach. Projects Time used and stretched skills the teachers of younger classes had been building for years, in both kids and adults. So they understood it—teachers and students both.

To the left, a group of students have been exploring construction techniques, ways of supporting weight for example, by creating miniature buildings with natural materials from the slope near our deck.

To the left, a group of students have been exploring construction techniques, ways of supporting weight for example, by creating miniature buildings with natural materials from the slope near our deck.

Still, people who didn’t see it in action found Projects Time perplexing. Parents new to the school sometimes expressed bafflement, until they had an opportunity to join us–or until talkative kids came home bubbling over. If new administrators never came to observe, they might be reassured by the testimonials of other staff, or by reading my parent letters–or they might not.

Most challenging of all, though, for me and for them: teachers from other schools might never have observed projects learning, let alone our situation of groups working parallel on different activities. When I talked with them at conferences and workshops–or family reunions, train rides, all those informal workshops teachers create for themselves—they said,  “Wait– if kids are working away from you, in a small group by themselves or with another adult, how can you be sure what they’re learning? If they’re not all following the same activities, how can you control what’s happening? What do you put on tests?”

“Wait– if kids are working away from you, in a small group by themselves or with another adult, how can you be sure what they’re learning? If they’re not all following the same activities, how can you control what’s happening? What do you put on tests?”

In the early years, faced with questions like these, I had to work hard not to get defensive. (It didn’t help that I had no idea how to explain serious playfulness. I just knew it felt right, and worked.) Then, as I developed more and more confidence in my students, I struggled to suppress anger at what I saw as lack of respect for kids.

In the early years, faced with questions like these, I had to work hard not to get defensive. (It didn’t help that I had no idea how to explain serious playfulness. I just knew it felt right, and worked.) Then, as I developed more and more confidence in my students, I struggled to suppress anger at what I saw as lack of respect for kids.

Eventually, though, I felt sympathetic. As years went by, I increasingly wanted to do one of two things.

-

I wanted to wave a magic wand and give these other teachers my opportunities for knowing students well. My class size, for starters—never more than 18, and more typically 15. Also, my self-contained class, together and with me for most of the day, except for specials and in some cases math. We shared a continuity, richness, and intimacy of group experience increasingly uncommon in the school lives of ten-to-twelve-year-olds. I could know both individuals and the chemistry of a group—know them really well—and that let me sense the ways I could trust them, and then build on that.

-

Sometimes I just wanted to loan out my inquiry-proficient students to these other teachers, as an example. You have to watch kids who are accustomed to belonging to themselves (like Mister Dog in the wonderful Little Golden Book by Margaret Wise Brown) in order to realize what they can do—what challenges you can give them, and what motivation they will bring to open-ended opportunities.

Sometimes I just wanted to loan out my inquiry-proficient students to these other teachers, as an example. You have to watch kids who are accustomed to belonging to themselves (like Mister Dog in the wonderful Little Golden Book by Margaret Wise Brown) in order to realize what they can do—what challenges you can give them, and what motivation they will bring to open-ended opportunities.

We did have in place a number of routines to keep me informed about how things were going, for groups as a whole, and for individual kids, and for the other adults in the situation.

-

Whenever possible, I built in freedom for myself to move from group to group, for at least some part of every time block, taking both notes and photographs as I went. (Otherwise, would I have this treasured shot of Lucy Candib and her group digging a hole under the deck, in which to bury various materials, which next year’s class would dig up again, in an ongoing year-after-year investigation called What Rots?)

-

I asked assistants and volunteers to fill out a quick question sheet at the end of each session, to help keep me informed. (They had time to do this while I led the final wrap-up.)

I asked assistants and volunteers to fill out a quick question sheet at the end of each session, to help keep me informed. (They had time to do this while I led the final wrap-up.) -

Students took notes and made sketches during Projects Time, and then wrote more afterward, summarizing what they’d learned, making additional drawings, listing questions. Sometimes I saw this writing over their shoulders, as groups shared at the beginning of the next session. Sometimes I collected students’ writing, to look for growth and for areas of confusion that needed support. When Sally Kent told me about lab notebooks with carbon sheets that could be torn out, we began using those, and kids could keep the original in their notebook for future reference, and give me the copies.

Students took notes and made sketches during Projects Time, and then wrote more afterward, summarizing what they’d learned, making additional drawings, listing questions. Sometimes I saw this writing over their shoulders, as groups shared at the beginning of the next session. Sometimes I collected students’ writing, to look for growth and for areas of confusion that needed support. When Sally Kent told me about lab notebooks with carbon sheets that could be torn out, we began using those, and kids could keep the original in their notebook for future reference, and give me the copies.

Still, our ways of observing and guiding students were premised on trust, meant to help us support students in their learning, not grade them on it. (Here’s more about that.)

Looking back, in the light of the current obsession with accountability, I realize that skeptical questioners were asking, ‟How do you keep the kids accountable?”

We worry about holding people accountable when we don’t think they’re likely to stick to their side of a bargain, or approach their part of a task conscientiously, or own some effort. We worry about accountability when we think people are likely to cheat—and people cheat when they don’t feel ownership of the results. Many things can lead to that lack of ownership—some of them outside a teacher’s power to intervene. People cheat when they’re depressed, when they’re overtired, when they lack confidence in what they can really do. There’s a lot to understand in that vicious circle, but demands for accountability don’t change it in any useful way. Or that’s how it looks to me.

Recently, I reread an essay in The Atlantic about why it’s so hard for American educators to understand the success of Finnish education. The article, by Anu Partanen, quotes Pasi Sahlberg, speaking to an audience at Teacher’s College in New York City in 2011. ‟Accountability,” he said, ‟is something that is left when responsibility has been subtracted.”

I keep mulling that over. I still have questions about Projects Time, and plenty of ideas for changes I’ll make and new things I’ll try if time travel ever becomes available. Still, Sahlberg’s statement helps me understand why Projects Time worked so well almost all the time; why my structures and routines for staying informed were secondary, in fact, to the most important part of the dynamic.

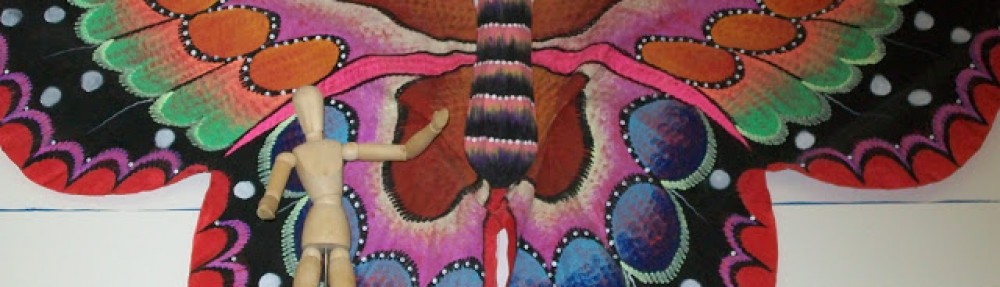

In Projects Time, students were genuinely responsible to each other. They were mutually responsible for the thoroughness and spirit, the seriousness playfulness, of their own groups’ inquiries, obviously. Beyond that, because they so often carried out different inquiries, in parallel, they were learning on each others’ behalf. They put creative thought and boundless energy into the ways they would demonstrate their methods and summarize their outcomes. For example, often they set up stations for other students to try out. To the right, a skit created by a group who’d been researching transportation access issues for people with physical disabilities.

would demonstrate their methods and summarize their outcomes. For example, often they set up stations for other students to try out. To the right, a skit created by a group who’d been researching transportation access issues for people with physical disabilities.

And then there were the puppet shows about water power, or future careers in transportation planning, or…

So there it is: Irony Alert. The same five-ring circus, the same level of complication that stretched the adults’ ability to be everywhere at once, meant that we didn’t have to.

We didn’t have to hold them all accountable, minute to minute. We held them responsible, instead, and they rose to that, for themselves and for each other.

And, as Robert Frost would say, ‟that has made all the difference.”

For this post, I’ve scanned in some older photographs I found when I went hunting for artifacts from the early years of Projects Time. These kids are now very grown-up grown-ups–finishing med school, having babies, beginning careers in agricultural engineering, as many stories as people. I look at the photographs and grin, and feel–for the millionth time–how incredibly lucky I was to know them when they were prototypes of the energetic, engaged adults they’ve become. So, all of you, thank you again.

I am jealous. So much of that sounds like it would have been fantastic as a student, or even as a parent volunteer — so much better than the crowd control I was asked to do as a parent volunteer in my kids’ schools. Also: oh my goodness, I am completely captivated by that “What Rots?” idea. I hope I’ll remember to do that with grandchildren someday.