The enigma of time

In a new novel by Kirkpatrick Hill, Bo at Ballard Creek, a gold miner who loves rocks, shiny or not, tries to tell Bo how old they are.

“They’ve been here since the beginning. Before plants or animals. Before the oceans. They’re billions of years old.”

Bo…looked hard at Peter’s kind face to see how old that was. Billions must be terribly old, but she couldn’t even imagine being twelve or fifteen, so how could she think of billions?

Bo is just five, but kids twice her age, or more–adults, even–have the same trouble. Trying to grasp the idea of deep time, billions of years of time, is like thinking of the depth of the universe—something always there, but mostly invisible to us, unreal even when we try hard to get our minds around it.

We need to grasp the depth of time in order to understand the role of evolution in biology, the impact of the speed of light in astronomy, any explanation of rock origins in geology, and the long span of cultural evolution in anthropology–just for starters. How can young adolescents begin to grasp this essential ground for so much learning?

Kate Keller, curriculum genius, on the case

Having grown up with multiple brothers and multiple sisters, Kate is interested in everything. (Even football, I think to myself as I write this.) The daughter of two architects, she is always alert to purpose and design wound together. Planning curriculum, reading everything she can find, Kate becomes a sort of settling pan (notice the gold-mining image) for the most powerful, most fertile, heaviest ideas in a thematic study–from some points of view, the most adult understandings. Then she comes up with active, playful, open-ended, deeply kid-centered ways for students to connect with these ideas.

All of us who work with Kate–colleagues, students, parents–feel smarter when we’re working with her. We try harder things, and try harder while we’re doing them. Not all geniuses have that effect.

We called our thematic study The Journey of Man but wanted it to encompass more than Spencer Wells’s book by the same title. We’d begin with a relatively brief overview of the past 5 million years of hominid evolution in Africa. Then we’d look at the past 50,000 years, focusing on the spread of modern humans, Homo sapiens sapiens, across the continents, using that as a chance to do a lot of geography work. Finally we’d look at the most recent 500 years of immigration into North America.

In other words, to think about all this, Kate and I wanted our students to imagine millions of years, thousands of years, and hundreds of years. How?

Modeling time and space

In order to make maps or scaled blueprints, we model large quantities of space by using smaller quantities of space. We let an inch equal a mile, or a centimeter equal a kilometer, or three, or a thousand. Here’s a very basic example from a favorite book about maps, by Harvey Weiss.

In order to make maps or scaled blueprints, we model large quantities of space by using smaller quantities of space. We let an inch equal a mile, or a centimeter equal a kilometer, or three, or a thousand. Here’s a very basic example from a favorite book about maps, by Harvey Weiss.

When we’re making time lines, we use small amounts of space to model large amounts of time. If a meter is a century, for example, then each centimeter is a year, and 10 meters can be a thousand years, a millennium. Need more than a thousand years? No room for a timeline 10 meters long? Change your scale. Let every millimeter represent a year, say, so that a whole meter stands for 1000 years. On the sample below, students made each 4 inches equal 100,000 years.

One way or another, a time line lets space stand for time.

Time lines can be very powerful. Here’s a memory I treasure, from another study. We’d been working on a time line of transportation innovations, and it had gotten so long that the students working on it had to lay it out down the school’s longest hallway. As I helped them carrying it back to our classroom at the end of projects time, some younger students walked by. “What’s that?” one asked. Without missing a beat, one of my students answered, “Ten thousand years of human history.”

On beyond time lines: letting time stand for time

Still, time lines aren’t made of time. Kate asked, “What if we let small quantities of time stand for longer quantities of time?”

Science videos sometimes present this in words. For example, at the beginning of the video The Journey of Man, Spencer Wells represents the evolutionary history of apes as one year, with the emergence of our own species, Homo sapiens sapiens, on December 28. This compression, in which we leave Africa on New Year’s Eve, can give kids some sense of the comparative brevity of human experience. But what could help them really feel it?

Suddenly, Kate came up with an idea so brilliant that the students who were involved still say it with an exclamation point: the time claps!

We would all clap hands, as a group, to represent time ticking away. The interval between claps, a few seconds, would stand for a much longer amount of time–a different amount of time in the time clap for each section of our study. Meanwhile, individual students would stand and move around and hold signs or other props, to represent what was happening within that time. We would all be participants, and all be watchers.

Some overall nuts and bolts

We did three separate time claps, each with a different scale and its own companion paper timeline, for the three parts of our study.

We worked in many ways to prepare for each of the time clap “performances.” We created paper continents and paper timelines and other props. At one point we arranged our desk groups into a very rough representation of the continents and their relation to each other, to help with that part. We made plays about the indigenous people of some of the continents, and investigated some of the requisite technologies for leaving the tropics. (In another post I need to write about the incredible contributions of parent volunteers, in all this hands-on work.)

Although we gave students the responsibility, as usual, for figuring out workable scales for the paper time lines, Kate and I figured out the scales for the time claps behind the scenes.

Here’s a chart I made as we were talking and considering:

The first time we tried it, we realized that counting 5 seconds again and again was much too awkward. (Try it–you’ll see.) The rhythm of “clap, two, three, four” worked much better, so we refigured:

The first time we tried it, we realized that counting 5 seconds again and again was much too awkward. (Try it–you’ll see.) The rhythm of “clap, two, three, four” worked much better, so we refigured:

Five million years

Five million years

For the first time clap, we looked at the past 5 million years of evolution of various hominin species. With everyone clapping together, we clapped and counted four seconds–clap, two, three, four, and repeat. Every eight seconds, or every two claps, counted as one tenth of a million years, 100,000 years. So we represented 5,000,000 years in 8 X 50 or 400 seconds, or 6 minutes and 40 seconds.

Meanwhile, different kids represented different hominin species. When the fossil record indicates the beginning of a species’ time, a student would stand up, holding a sign with that species’ name. He or she would stay standing for as long as that species is thought to have been around, and act out some of the behavior scientists agree we had evolved at that point: creation of stone tools, use of fire, ritual burial of the dead.

So, for example, the student representing Homo erectus stood up around 1.8 million years ago (represented on the time line as 1.8 MYA, and in the clapping as 65 claps in, since we began with a clap.) Then he or she sat back down at roughly 27,000 years ago, two seconds before the end.

On the time line, the kids put the label for Homo erectus about halfway through that species’ time, and used a yellow line to represent the whole Homo genus.

In that first time clap, long stretches went by, during the first few million years, between the emergence of known hominin species. A lot happened pretty quickly in the last 200,000 years, represented by the last 16 seconds.

Kate wanted students to feel the way a simple list of events doesn’t give a true sense of their relation in time. It takes some way of making the intervals proportional to the actual intervals, to get a real sense of the depth of time we’re talking about when we look back that far.

It takes the passage of time to help us imagine the passage of time.

Speaking of which…

Writing a blog resembles teaching in some ways: everything takes so much longer than you think it will, and personal excitement can make it take even longer. We all loved this work; we felt proud to be doing something we’d never heard of students this age doing. I saved lots of notes and lots of artifacts. I want to share some of them, but I also want room for some thoughts Kate and I had when we talked about all this recently. In other words, this post has become, itself, a time line for which I have no adequate hallway.

So, I’m throwing my hands in the air, and stopping here. Next post: 50,000 years, and 500 years, and what we think, looking back.

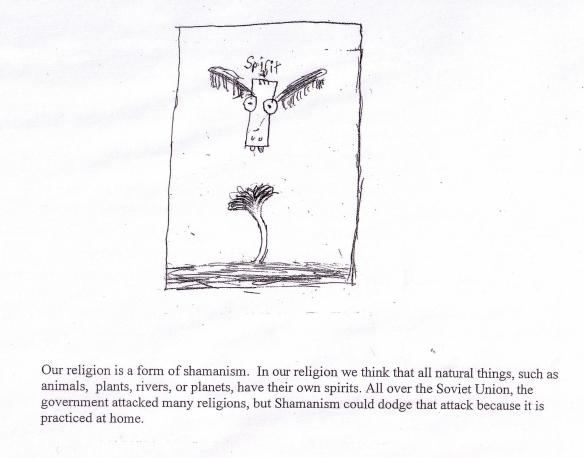

I also want to mention that when I searched through those artifacts I found a copy of our picture book about the Chukchi, and added some wonderful samples of that to the previous post. The benefits of boxpile archaeology.

In more recent years, we’ve used a BBC video series, The Incredible Human Journey, which follows Alice Roberts, a British medical doctor, anatomist, and anthropologist, as she travels from continent to continent searching for evidence and meeting with scientists from many disciplines, to understand the history of our own species, modern humans.

In more recent years, we’ve used a BBC video series, The Incredible Human Journey, which follows Alice Roberts, a British medical doctor, anatomist, and anthropologist, as she travels from continent to continent searching for evidence and meeting with scientists from many disciplines, to understand the history of our own species, modern humans. She crosses from one Indonesian island to another on a bamboo raft built entirely with technology that would have been available to ancient people. She considers the evidence of ancient human occupation on an island off California that could only have been reached by boat, providing support for the theory that many of the earliest North Americans paddled here, around the coastline.

She crosses from one Indonesian island to another on a bamboo raft built entirely with technology that would have been available to ancient people. She considers the evidence of ancient human occupation on an island off California that could only have been reached by boat, providing support for the theory that many of the earliest North Americans paddled here, around the coastline.