My Year to Think It Over took almost two years, actually. Every week or so I looked through my overflowing boxes of teaching souvenirs, revisited twenty-five years of life in an extraordinary learning community, and returned to these questions:

- What did I learn, over time, about collaborating with young adolescents?

- What learning adventures were particularly memorable, and what seems to have helped them work?

- What am I still learning from the comments of past students, now adults?

- What can I give back, out of the gift of all that time doing what I loved best?

When I started the blog, I had stopped teaching. Finally I could write more: savor wonderful moments, and reflect on them; give credit to people who deserved it; give voice to ideas and practices that had guided me; honor students whose descriptions of their experience had transformed mine.

When I started the blog, I had stopped teaching. Finally I could write more: savor wonderful moments, and reflect on them; give credit to people who deserved it; give voice to ideas and practices that had guided me; honor students whose descriptions of their experience had transformed mine.

I began writing posts one by one without any realistic schedule–I really thought a year would do it!–and without any overall plan. Very soon threads of continuity began to emerge, willy-nilly, and those stretch across the screen up at the top, below the butterfly.

If you click on those headings, you’ll find an introduction to each strand, with links to posts exploring that strand. You can also click on the topic headings below.

Power in Literacy I worked mostly with kids who were 11 or 12 years old. Often, in our mixed-age class, I spent two years with students. Across any time we had, students developed real and flexible fluency as readers and writers. With increasing confidence, they used reading and writing to explore the world and their own emerging identities. This heading title includes the word power, because that’s what I saw: I watched kids–in a world and at an age in which they can so easily feel powerless–taking up the effectively magical powers of literacy with contagious pleasure.

Power in Literacy I worked mostly with kids who were 11 or 12 years old. Often, in our mixed-age class, I spent two years with students. Across any time we had, students developed real and flexible fluency as readers and writers. With increasing confidence, they used reading and writing to explore the world and their own emerging identities. This heading title includes the word power, because that’s what I saw: I watched kids–in a world and at an age in which they can so easily feel powerless–taking up the effectively magical powers of literacy with contagious pleasure.

Being Human Within an interdisciplinary approach, we could draw on both science and social studies–and anything else–to explore our human evolution and the voyage leading to who we are. We could grapple with issues our species still struggles to work out, about how to live together. Eventually, students often dragging me along, we arrived at questions this basic: “Can we come to see each other, all over the world, as cousins? Over time, could that change the way we view the notion of race? Or the costs of war? Or the goals of economies and governments and communities?” If you give them the chance, young adolescents will tackle amazing things.

Being Human Within an interdisciplinary approach, we could draw on both science and social studies–and anything else–to explore our human evolution and the voyage leading to who we are. We could grapple with issues our species still struggles to work out, about how to live together. Eventually, students often dragging me along, we arrived at questions this basic: “Can we come to see each other, all over the world, as cousins? Over time, could that change the way we view the notion of race? Or the costs of war? Or the goals of economies and governments and communities?” If you give them the chance, young adolescents will tackle amazing things.

A Sense of Place What do we mean by “a sense of place” or “place-based education”? What can kids gain from exploring and coming to know the places they call home, and the places they share with others, including school? How far can a vivid sense of place reach, and what skills support that reaching? How can we respect and honor–and take responsibility for–the places that nourish us? These posts explore the teaching and learning of geography in its largest meanings.

A Sense of Place What do we mean by “a sense of place” or “place-based education”? What can kids gain from exploring and coming to know the places they call home, and the places they share with others, including school? How far can a vivid sense of place reach, and what skills support that reaching? How can we respect and honor–and take responsibility for–the places that nourish us? These posts explore the teaching and learning of geography in its largest meanings.

Serious Playfulness Here I gathered posts about our explorations of mathematics,  various branches of science, and some related matters. Obviously “serious playfulness” is my own wacky term, but it means what it says: we were serious in our goals, but the ways we pursued them were playful oftener than not. Playful didn’t mean games based on television quiz shows. It meant true inquiry; open-ended questions; working together, taking risks, and getting dirty; discovery and surprise.

various branches of science, and some related matters. Obviously “serious playfulness” is my own wacky term, but it means what it says: we were serious in our goals, but the ways we pursued them were playful oftener than not. Playful didn’t mean games based on television quiz shows. It meant true inquiry; open-ended questions; working together, taking risks, and getting dirty; discovery and surprise.

Together This overview gathers posts that explore social and emotional learning: learning to care for each other, learning skills for working in a group, learning both kindness and resiliency. This strand also includes a series of posts about not using grades, because, in our experience, other kinds of assessment worked better to support authentic collaboration and community.

Together This overview gathers posts that explore social and emotional learning: learning to care for each other, learning skills for working in a group, learning both kindness and resiliency. This strand also includes a series of posts about not using grades, because, in our experience, other kinds of assessment worked better to support authentic collaboration and community.

When I first began this blog, and composed the About page, I wrote out of that clarity that can come from life in the trenches. “The world is full and busy and loud with ideologies about what works in education. I want to revisit some real experiences that worked for real live students, and think about why and how.”

When I first began this blog, and composed the About page, I wrote out of that clarity that can come from life in the trenches. “The world is full and busy and loud with ideologies about what works in education. I want to revisit some real experiences that worked for real live students, and think about why and how.”

It would be thrilling if my school’s approaches became–soon!–the norm not only in published research results, but also in mainstream practice. None of us should hold our breath. In the uphill battles we still face, I’m going to keep these posts available as long as they seem to be useful. Rereading, I’m deeply grateful for both experiences: to have lived that richly challenging and rewarding teaching life, and to have taken the time to “think it over” afterwards. I’m grateful to everyone who felt that this was an important thing for me to do, and said, “You can do it.” (Alex Brown, you’re at the top of that list.)

Through this writing, things I’d learned from teaching reached forward into my present. Attending writing workshops at UMass Boston’s William Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Social Consequences, I felt again how overwhelming and exhilarating learning can be for the learner. Visiting my dad as he slipped further into dementia and spoke much less, I watched him learn to play a game oriented around spatial relationships. My math teacher self talked to my daughter self, helping her.

Through this writing, things I’d learned from teaching reached forward into my present. Attending writing workshops at UMass Boston’s William Joiner Institute for the Study of War and Social Consequences, I felt again how overwhelming and exhilarating learning can be for the learner. Visiting my dad as he slipped further into dementia and spoke much less, I watched him learn to play a game oriented around spatial relationships. My math teacher self talked to my daughter self, helping her.

Am I done here? I’m not sure. I haven’t explored some topics, or told some stories that feel important. But at this point I am more involved in other adventures.

Meanwhile, however you’ve found this blog, I’m glad. I feel like the host of a fabulous potluck feast. In effect, I’ve spent years working with wonderful cooks. Enjoy! Be emboldened! You can reach me, if you want, at the most obvious email address for someone named Polly Brown. I don’t like to write it out, because robots search for such things–but you’re very unlikely to guess wrong. Or you can share a comment.

From my new adventures, I wish you well in whatever you may be exploring or daring to try, in your own learning life.

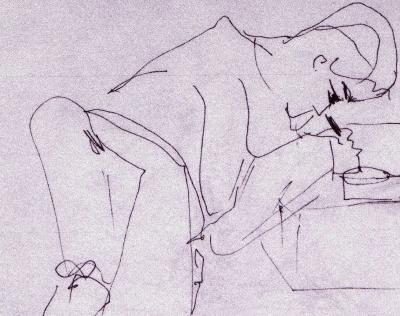

mates that same way. But I knew how tricky this could be in a school drawing its population from a whole region, not just a neighborhood. We needed to build the neighborhood feeling at school, every chance we could get. To the left, Amy Bouman works with one of her daughter’s classmates, Sam Winalski, to create special clothing for that year’s Alhambra Banquet.

mates that same way. But I knew how tricky this could be in a school drawing its population from a whole region, not just a neighborhood. We needed to build the neighborhood feeling at school, every chance we could get. To the left, Amy Bouman works with one of her daughter’s classmates, Sam Winalski, to create special clothing for that year’s Alhambra Banquet.

vation called chicken tractors. We became a sort of business incubator for new ideas about agriculture, young-adolescent-style, with the prototypes made in sculpey and found materials, for displays to teach the rest of the class.

vation called chicken tractors. We became a sort of business incubator for new ideas about agriculture, young-adolescent-style, with the prototypes made in sculpey and found materials, for displays to teach the rest of the class.