“I’ll tell you the truth,” he said. “If I don’t know the person I’m sitting near–especially if it’s a guy–I keep having the impulse to punch him. It’s hard to pay attention to anything else.”

There it is, laid out as clearly as possible, as only a kid could. He might have felt this unusually vividly, and expressed it to me, one-on-one, unusually straightforwardly. Still, there was some element of his feeling in many of his classmates. Students prefer to be seated near other students they know. Left to their own devices, most kids aren’t particularly eager to reach out to unfamiliar people.

Hooray for the minority who do reach out in friendship, and the huge gift they give to the group! Still, most kids need help with that.

Class life should give them that help. Here’s a corollary of my student’s statement. Students need to get to know the other members of a new class fairly quickly, so they’re not each sitting in the wanting-to-punch-someone condition (or some individual variation of that.) The teacher’s structuring of the situation needs to support kids in creating social inclusiveness, mutual knowledge, and safety, so that other good things can happen, things like learning how to divide fractions, or when to use there, they’re, and their–or the history of immigration policy, which is all about exclusion and inclusion.

Ideally, a teacher works gently and carefully with whatever social chemistry she or he finds, to create a productive balance of secure familiarity and growth-nurturing newness, for every student.

Among the faculty of my small school, all of whom I respected, there were real differences of opinion about how to work this out. Different routines are appropriate at different ages; different strategies work for different teachers’ styles.

Beginning the year

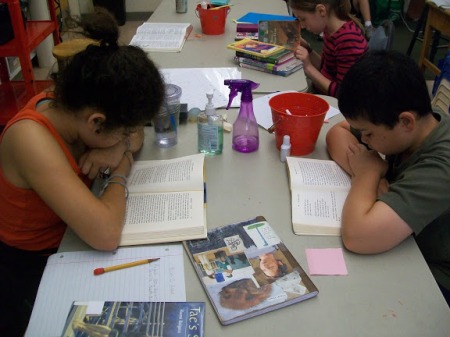

My young adolescent students (aged ten to twelve) spent a lot of their day moving around. Still, their table places were very important to them.

Before the first day of school, I made a temporary seating chart, and signs to put at students’ places. Kids would be seated at tables that held four students, and this usually worked out to be three or four at each table. (Longer ago, these were desk clusters with about the same number of desks in each cluster.)

Before I made this temporary arrangement, I talked with the teachers who were sending kids on to me. I always felt grateful for the help this gave me. I didn’t want the job of inclusion to fall to just a few generous kids. I tried to avoid giving hard jobs to kids with challenged attention, or to kids with sensory integration issues who might be thrown off by classmates brushing against their chairs. I thought carefully about how to handle kids with desperate crushes. (“Please,” a girl said to me when she ran into me over the summer, “don’t put me where I’m looking directly at _____, ” She knew herself, and knew what I needed to do for her.)

I tried to build in unfamiliarity along with familiarity. For example, I wouldn’t put three close friends at the same table–not good for them, not good for the group. I wanted everyone to have some safety, and some reaching to do.

As the year moved forward, the groupings for academic work often built social connections. For example, projects time groupings were generated by kids’ choices of the various activities, expressed in rankings on sticky notes (which I could easily move around to arrange the groups.) It’s a tribute to the social education of my students before they reached me, that they could almost always handle this. For two afternoons a week, they could work in a small group with anyone, and make it productive. It was enough to have shared interest in a topic and a hands-on activity, with a little support from me or from a parent volunteer.

As the year moved forward, the groupings for academic work often built social connections. For example, projects time groupings were generated by kids’ choices of the various activities, expressed in rankings on sticky notes (which I could easily move around to arrange the groups.) It’s a tribute to the social education of my students before they reached me, that they could almost always handle this. For two afternoons a week, they could work in a small group with anyone, and make it productive. It was enough to have shared interest in a topic and a hands-on activity, with a little support from me or from a parent volunteer.

Very often, new friendships came out of these projects time pairings or groupings–if not close over-each-other’s-houses-frequently friendships, at least I’ll-put-this-person-on-my-list friendships.

The list

About a month into the year, sometimes less and sometimes more, I followed the seat assignment ritual I had learned from Kate Keller.

First we talked about the guidelines:

- List at least two people of each gender. It’s fine to list more than two.

- It’s okay to say “any boy” or “any girl” but you have to mean it, and that will count as meeting your conditions.

- You can’t say “any girl (or boy) except _______.”

- It’s fine to say “anybody.”

Kids wrote their preferences on 3 by 5 cards, with their names at the top. I learned that I needed to talk about anyone who was absent, so the card-writing kids wouldn’t forget about that person. It was helpful, especially early in the year, to have all the class names visible. Students folded the file cards and brought them to me, and I treated them as if they were top secret files from the CIA.

On the same cards, kids could also write requests involving placement in the room. I tried to honor those requests, if I could, since I wanted to encourage the self-knowledge that often went into them. I explained ahead of time, though, that I couldn’t make promises, because good social mixing had to stay my main priority.

I promised just this: to give each student one person from his or her list, seated nearby. One safe presence.

That was hard enough to do, sometimes–to make all those interlocking choices work out. Usually, I started making the arrangement by placing kids who were least chosen by the others, or those who weren’t chosen by people they’d chosen themselves. They needed support, and this was one way I could give it.

One year, by the end of the year, every single file card said “anybody.” Thrilled and impressed, I threw them an ice cream party over the summer to express my high regard.

A sociologist could write a book about how these table-mate choices evolved through the year, with a chapter about how friendly, undemanding students tended to be chosen by almost everyone, time after time, and another chapter about how a child working hard to enter what he perceived as a popular group would fail to list any of the ordinary kids who had listed him and might treat him better. We don’t come automatically equipped with social skills for classroom life; we have to learn them, together, with some detours and lots of support. The information on the cards helped me know where support was needed.

Occasionally, a student thought she was designing the table group of her dreams, and reacted with shock when she didn’t get all of the people she had listed.

How to avoid any open expression of shock or dismay:

This sounds goofy, but it helped. Before I announced the seat assignments, or projects time groups, or any situation in which kids were placed in groups (almost always with their input) we went through the Ah Yippee ritual. This is very hard to describe in words. If you’re lucky enough to know a student from the past ten years, he or she may be willing to demonstrate, but it’s pretty silly.

Following a hand signal, we all said Ahhhhhhhhhhhh Yippppppppeeeeee! (Do you know what I’d give for a tiny video of this?) The collective tone swooped around, down and then back up. In the process, each child expressed his or her disappointment and excitement about the grouping–before knowing it.

Why in advance, before they knew? So the actual groupmates, or others not in a welcomed group, wouldn’t feel dissed.

We switched table places four or five times through the course of the year. Meanwhile, there were more frequent switches of math partners and projects time partners. All this in addition to various group-building activities I’ll describe another time. They helped, too–but my best chances at constructive social engineering were mostly under the students’ radar, in careful decisions about who sat where, and who partnered whom.

One way and another, there were lots of opportunities to decide that the unknown person you thought you wanted to punch might actually be someone you could trust and enjoy.

Hooray for the everyday bravery of kids in classroom life! Hooray for all the rewards it brings them!