A few weeks ago, Chrissy Danko and I met for lunch. Every time I’ve thought about it since then I’ve started grinning. She is the oldest of four siblings, and I taught them all, sad to say goodbye to the last of them and to their parents. (‟Wouldn’t you like to have more?” I asked Joe and Joan, impertinent as ever.) It was a huge treat to sit and talk with Chrissy, and hear about them all, and hear about who she’s becoming as an adult.

When she came to me, Chrissy was so shy she barely spoke in front of the class. My fierce protection of turn-taking, especially for the turns of the quiet, didn’t work for everyone, but it helped Chrissy. She opened up; she began to appreciate herself more. Now she is writing her dissertation, for a PhD in philosophy, about Hume and Kierkegaard–and about what it means to be an individual, to have a self.

Here’s a photograph of Chrissy, when she was in my class:

Here’s another, at Halloween. I have no idea who’s the alien, and who’s the pumpkinhead, and would love to know. (At a place that really values creativity, Halloween can be pretty amazing.)

I don’t know how it is in your life, oh patient reader, but in mine, right now, there are many mysteries, treasures that lie somewhere unknown in still-pretty-tall stacks of boxes. Some absences I can live with cheerfully for a while more, but some feel like serious deprivations. For example, although I saw it some time in the last year, I can’t find Chrissy’s ancestor pie. Hers was one of the most unique of the circle graphs of background and heritage that I assigned in the early years of the immigration theme.

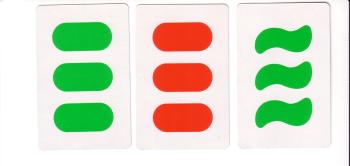

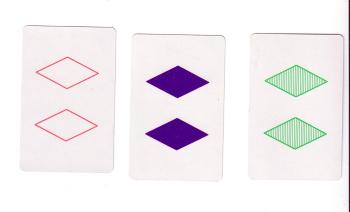

Here’s Aaron Goodman’s ancestor pie, made that same year, also quite wonderful:

Pretty soon in the evolution of the immigration theme, I stopped assigning ancestor pies, realizing that they could be problematic for some kids. While it was an assignment, though—and later, when it was a choice—we considered fractions as small as sixteenths, one sixteenth for each of a child’s sixteen great-great-grandparents. Two parents; four grandparents; eight great-grandparents; sixteen great-great-grandparents.

(When I heard that a cousin in my father’s Maine hometown had said that his great-grandmother had been two-thirds Indian, I knew that couldn’t be quite the case. Ancestry denominators come in powers of two.)

Aaron didn’t need sixteenths; fourths did it for him. Ben Redden needed eighths, and managed to line up the eighths from two different grandparents, to show that he added up to a fourth English.

For Chrissy’s ancestor pie, unique and memorable, she made one big pink circle, on which she wrote, ‟I’m all Polish.”

On one of those trips back from Ellis Island described in the previous post, Chrissy’s dad’s stories intrigued me. More accurately, I was struck by his lack of stories. ‟They won’t talk about it,” he said. ‟None of them will, or ever would.” The memories of life in Poland too dark? Or still too much sense of rupture from that other life? Maybe both—since those feelings seem able to coexist, in all of us.

Another parent had spent years coming to understand that her mother’s grimness could be traced to her own mother’s very difficult immigration experience. She’d been left behind as a baby, then finally came over to join her family, and was ridiculed for being slow to catch on to America; her bitterness affected her daughter. ‟I’m where it stops,” my student’s mother said. ‟I’m not going to keep living out that hurt, and I won’t pass it on to my daughter.” (I may not have the family history details quite right, but I will never forget the mother’s resolve.)

Even the stories we would definitely call successes seemed often to have a shadow.

Beyond those individual stories, looking at the community story, I began to see the melting pot project as very much unfinished, at least in our area. A friend of mine in Marlborough went to have her children baptized. ‟Wrong church,” they told her. ‟You’re Irish. This is the Italian church.” Several Worcester parents in my class described lingering enmity between Irish Catholic and French-Canadian Catholic colleges.

These and other stories convinced me that we can all be tribal, insular, distrustful. We seem to be nowhere near being able to handle racial differences; we can’t even handle ethnic ones.

(All of these, of course, being cultural constructs, not biological. Inside that designation of Polish there could be many variations, given Poland’s history. And we are all Africans, in very recent time. But that’s for another post, somewhere down the road.)

The ancestor pies told yet another story. Sarah Tonry’s, one of those mysteries hidden in the boxes, had nine colors, as I remember, for nine different flavors of European heritage. Most of the kids in our central Massachusetts population colored in at least three or four different cultural origins, and when we located all our collective countries of origin on maps, the class list ran to nearly twenty, easily.

Willy nilly, we were the melting pot, and the ancestor pies showed us that.

I myself have to go to fractions smaller than sixteenths to show anything other than one big circle. Growing up, surrounded by people with ‟interesting fractions,” I felt the lack severely. At some point, our mother helped my sister and me calculate that we were 1/2048th French. An exhilarating notion. We spent a whole crossing of Long Island Sound gloating.

Family legend in my father’s family said that we were 1/16th Native American, and recent research by family genealogists indicates that my generation probably really is 1/32nd Abenaki. I’ve learned since that brutal treatment of Native American Indians in southern New England led survivors to flee north. So Judith, my great-great-grandmother, could have been any combination of tribes, along with whatever portion she had of what we call white.

I’ve thought about Judith a lot, remembering this again and again: inside our historical selves, the selves we bear through the changes and patterns and stories of history, there are wars. There are hurts unassuaged, that convey hurt forward without ever being named. For all of us, one way or another, things got thrown overboard; loved people were left behind.

Publicly, we may celebrate our emigree identities, whatever they may be, and the melting pot project, the meetings of differences. Privately we still seem to carry a lot of grief, more than we usually let ourselves know.

That’s one of the things the community of a class can do together: we can honor each others’ historical selves, whatever we know and share of them. Honor them with knowledge and wide understanding of the historical context; celebrate them with respect and joy. We can be gentle with the unnamed mysteries inside the tall stacks of unsorted boxes that are each of our identities.

One year, Kate Keller (wearing her aide hat) suggested that all of us take our just-finished immigrant mini-posters outside. (Each mini-poster gave the basic information about one immigrant, relative or friend, for each member of the class; Kate and I each made one, too.) Outside, we all stood together on the wide steps below the classroom windows, holding our posters and making a human timeline, century by century. A fairly boisterous crew, we stood there quietly for a minute or so, honoring all those reasons to have left and reasons to have arrived, all those ways of persisting afterwards. We called all those people, a few still living, most gone, to be present. Neither of the adults had dry eyes.

Living with each other, hearing each other’s stories, we might have looked pretty homogeneous to an outsider, but we were honoring difference, discovering commonality, keeping an old project alive. Nothing else we did mattered more.