The story so far: If the product of a learning experience takes the form of a grade, other possible products and outcomes have less reality and less power for the learner.

Voices speaking out against grades want to shift the focus of learners and teachers, to give priority to those other products and outcomes. I’m going to focus on just a few.

# 1 Teacher support, and student goal-setting, guided by targeted, individualized, meaningful assessments

Focused effort matters, and thoughtful assessment can support that. Very briefly, here are some of the kinds of feedback individual kids could come to expect in my classroom, in place of grades:

- one-on-one working conferences to look at pieces of writing, reading comprehension progress, math quiz outcomes, etc.;

- group mini-lessons based on common confusions or not-quite-there efforts or emerging possibilities or spontaneous break-throughs, acknowledging and moving forward from all those;

- quick skills checks in the form of miniboard warm-ups;

- written responses to specific assignments;

- long narrative progress reports twice a year;

- conversations in preparation for portfolio sharing, and the portfolio conferences themselves;

- feedback from classmates, students in the wider school community, parents, and other adult audiences.

The previous post has examples of some of these. The feedback for students in younger classes varied from this in developmentally appropriate ways, but always with the same goals: not judgment, but celebration and support.

Each of these activities provided an opportunity for student and teacher to observe patterns in comprehension and skill, or difficulty, and to set goals both short-term and long-term. At the same time, each of these assessment activities was an opportunity to revisit, share, and reconsider the important questions inherent in our content.

#2 Learners who belong to themselves

I remember a conversation with the high-school-aged daughter of a friend. She told me about her classes for that year by telling me her grades. She couldn’t tell me what was interesting to her; couldn’t say what she wanted to learn next; couldn’t describe anything about her learning process. Her grades were high overall, and she assumed that the subject in which she was getting the highest grades should be her major in college.

This young woman didn’t belong to herself as a learner; she belonged to her grades, and to the people who were giving her those grades–even the people who were celebrating those grades.

Especially once we were able to keep students until they were ready for high school, people observing the graduates of my school have been struck by the way graduating 14-year-old kids belong to themselves–how clearly they know and understand and respect themselves as learners.

Instead of pinning their student identities on their GPA, students in ungraded situations learn how to work with their real identities as learners. They learn how to choose meaningful and sustainable challenges for themselves. They know how to manage their own attention, and what to do to sharpen their memories. There may be passages through which they struggle, but a lot of the time they’re having a blast. Above all, they know, for themselves, why it matters. To the left, checking and graphing temperatures.

Instead of pinning their student identities on their GPA, students in ungraded situations learn how to work with their real identities as learners. They learn how to choose meaningful and sustainable challenges for themselves. They know how to manage their own attention, and what to do to sharpen their memories. There may be passages through which they struggle, but a lot of the time they’re having a blast. Above all, they know, for themselves, why it matters. To the left, checking and graphing temperatures.

#3 Authentic and rewarding group learning

Teamwork flourishes best when grades are out of the picture. When I’ve talked about the amount of group work happening in my class, people have often asked, “Don’t kids get distracted by working together? How can you tell who did what?”

I’d have to be crazy to deny that distraction happens sometimes, or that timid students can become dependent on others. Still, young adolescents are ready and eager to learn how to be teams.

At Tsongas Industrial History Center, these girls are constructing a working canal system model. As usual, museum educators commented on how well students worked together–incorporating everyone’s ideas, sharing the dirty work on the floor.

At Tsongas Industrial History Center, these girls are constructing a working canal system model. As usual, museum educators commented on how well students worked together–incorporating everyone’s ideas, sharing the dirty work on the floor.

At any age, effective group work doesn’t happen automatically. In order to get the huge benefits of several minds focused on the same task, complementing and helping and challenging each other, kids have to learn how to be task-focused and team-focused both at once; how to do the social work, the intellectual work, the creative work, and the procedural work all woven together.

Kids exposed to plenty of group projects in an ungraded situation get a terrific head start. Without grading to tell them they’re competing instead of collaborating, they learn how to stay balanced within the group process, and how to help the group stay balanced so it keeps on working for everyone.

If you want an argument against grades, focused on future success, you could start with that.

Above: Working with a parent volunteer, students help each other figure out which direction the rivers are flowing on topographic maps.

Above: Working with a parent volunteer, students help each other figure out which direction the rivers are flowing on topographic maps.

Meanwhile, freed from generating grades, I could put time into helping groups design and choose tasks that would engage them, with topics and audiences that mattered to them. The resulting energy helped their bicycle built for two (or three or four) keep momentum.

Often, when sharing work in a portfolio conference, students mentioned their partners and teammates, and told about what each of them had contributed, as I set off quiet internal fireworks of celebration. Yes!

# 4 Deep meanings held in community

As humans, we seem to have evolved to construct meaning, and experience meaning, collectively.

Many groups of students have been inspired by the collective power of the communities that built Stonehenge, and archaeologists’ ideas about the community events held there.

Many groups of students have been inspired by the collective power of the communities that built Stonehenge, and archaeologists’ ideas about the community events held there.

Archaeologists and paleo-anthropologists have found evidence of the power and importance of community life and community understanding, deep in the past history of our species–and even for the other hominin species before us.

Young adolescents work hard to begin to understand huge things: life and death, economic reality as they observe it, the concept of scale, the notion of one image symbolizing whole realms of experience. Whenever I asked groups of students what they’d like to understand better about the world, I was astonished anew at the ambition of their questions, knowing this at the same time: the really heavy lifting they can’t do alone, any more than adults can.

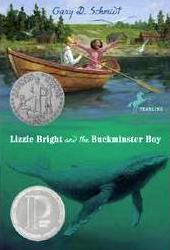

In my own most emblematic image of this, a group of learners listens to a challenging novel read aloud. As I write, I realize that I’m thinking particularly of Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy, a novel about racial prejudice in early 20th century New England, beautifully written by Gary Schmidt. Sharing a novel like this, the students build understanding together through their various comments and questions. Sometimes I sense their collective bravery in their silence for a tricky passage, or just after.

In my own most emblematic image of this, a group of learners listens to a challenging novel read aloud. As I write, I realize that I’m thinking particularly of Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy, a novel about racial prejudice in early 20th century New England, beautifully written by Gary Schmidt. Sharing a novel like this, the students build understanding together through their various comments and questions. Sometimes I sense their collective bravery in their silence for a tricky passage, or just after.

If somebody out there knows a way to assign grades to the quality of a shared group silence, let me know.

Now hold that in contrast to this: When individual achievement is the only test of an experience; when shared learning is considered cheating; when it’s constrained by the “level-playing-field” concept that requires teachers to do exactly the same things for every student; when teachers face such large classes that they have no way of knowing who’s doing what without completely isolated graded assessment–the deepest and truest parts of learning are hobbled, compromised, or outright lost.

It’s not impossible to nurture community, and the deep meanings community can hold, in the presence of a grading system–just harder. In fact, in my experience, over-emphasis on individual outcomes in any form–either grades or some supposedly benign substitute–works against the development of community, and the construction of shared meaning.

#5 Powerful connections with content

When grades aren’t the focus, content itself–the world!–gets more attention. The world is alarming to young adolescents–and to all of us–but also fascinating. Grades wind up being a smokescreen in the way of that fascination.

That’s what broke my heart about my friend’s daughter, mentioned earlier. She was experiencing very little actual engagement with the world and how it works and what we make of it. Her grades were like junk food, no fit substitute for actual encounters with the depth of time, or the mysteries of prime numbers, or the relationship between surface area and heat loss, or the way human history offers such contradictory evidence of both altruism and cruelty.

I think of a student long ago who wanted to read novels about the Holocaust. She had no assignment. She just kept coming back to me for more books, and talking about them to her classmates and parents. She was choosing her own path to a deeper understanding of the world.

Or I think of a student, now grown to a man, who used his sketchbook, during morning sketching time (which was completely open, unassigned), to make a very long narrative map, which continued from one two-page spread to the next, and the next, for months. The map as a whole incorporated everything that kid was noticing about the world through which he traveled: about geography, transportation, and the designs of buildings and other systems; about humor; about continuity and discontinuity.

Looking back, I remember now that this student’s family had just gone through an unusually messy divorce. His rehearsal of continuity in the built and natural worlds, page by turned-over page, feels tremendously poignant to me now. At the time, I was focused on his thinking and processing and creativity. But it seems likely, now, that the mapping was working for him on levels I couldn’t even guess. He gave himself the assignment that let him live in his intellectual strengths, and use those strengths to help him live through his family’s troubles.

Although he made me copies of some of the pages, I have no idea where they are. Hooray for memory so vivid and dear that it doesn’t need props. Hooray for learning so rich that no grade could encompass it. Hooray for the safe haven, also a highly effective launching pad, in which such work could happen.

I have a feeling I’m still not done with this topic…

I so wholeheartedly agree, and wish my kids had been exposed more to that kind of learning. I think some regular schools can, and do, offer enough collaborative experience to let kids see the value of learning that way. But the thing traditional schools of any caliber rarely do is help students with that critcial process of understanding who they are as learners, and then figuring out how to navigate the world with that particular mind and its unique ways of seeing and experiencing, with a toolbox that holds what matters to thrive. Learning oneself is such a crucial part of life — and yet somehow we expect kids to figure that out on their own without assistance or help even in conceptualizing what that means. As parents, we can try to fill that gap; but those efforts are not a real substitute for what teachers like you do in helping kids claim themselves, since most of us lack the insight, experience, vocabulary or framework to help effectively.

I’ve always thought that short of total revolution, traditional schools could at least dedicate meaningful time at all ages to the process of helping kids claim themselves, as you say, as learners — and as contributing members of a community. Just encouraging kids to reflect about such things with a little guidance can be a start. Small steps…