In the teaching and learning I’ve written about for this blog, some things never happened–things taken for granted in most schools. I was lucky.

For starters: because my school didn’t require me to, I never summarized my assessments of students’ work using grades. No number grades; no letter grades; none of the judgments about mastery (not as clear a concept as you might think) summed up in terms that are just grades thinly disguised. None, never, nada.

Like all my colleagues, I gave plenty of careful attention to student work. The students received many kinds of feedback, and even more kinds of support. Above all, in ways small and large, we celebrated the culmination of authentic learning. But not with grades.

Like all my colleagues, I gave plenty of careful attention to student work. The students received many kinds of feedback, and even more kinds of support. Above all, in ways small and large, we celebrated the culmination of authentic learning. But not with grades.

I was still a kid myself (and getting A’s) when I decided that grades were meaningless and dangerous. As an adult, I’ve been known to refer to grading as institutionalized child abuse.

Still, I’m used to the fact that people I respect may disagree. Occasionally, Touchstone families have decided they wanted grades, going somewhere else to get them. Other families have wished for the crispness of grades, but stayed for the quality of their children’s learning. Almost all our graduates have gone on to schools that use grades, and almost all of them have continued to belong to themselves and care most about meaning.

If you want to read essays about the uselessness (or outright harmfulness) of grades, track down the writings of Alfie Kohn. I think often of a less famous heroine, Meghan Southworth, a working math teacher and trainer for the Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance. She wasn’t able to eliminate all grades, because her school required them at the end of every quarter. In order to have some basis for those grades, she had to administer tests and other graded assessments, and record the results.

Here’s the kicker: she had stopped showing her students the grades they received through the term.

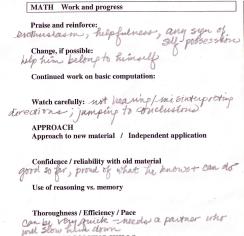

Instead, she continued to give her students written comments. I didn’t see hers, but I’m guessing they were a lot like mine: suggestions for ways to rethink problems, ways to improve quality control, ways to balance carefulness and momentum–along with acknowledgement of the kinds of engagement and effort, no matter how tentative, that can help a student move forward. Here’s a small sample of comments on a test:

This student was working to overcome test-taking anxiety, and needed to focus on how close she was to the full answer. Thus “almost” instead of an X.

This student was working to overcome test-taking anxiety, and needed to focus on how close she was to the full answer. Thus “almost” instead of an X.

Like most teachers everywhere, Southworth wanted her students to improve, not just stay at the level of achievement they arrived with. She had noticed that they wouldn’t really absorb or use the support embedded in her comments, as long as the shortcut of a grade was available. She quoted a student who caught on to her new system very quickly: “Oh, you want us to read the comments instead of just looking at the grades!”

Southworth also cited research describing most students’ response to grades: “Is this what I’m used to getting?” If the student is used to getting A’s, and this is an A, no need to stretch. If the student is used to getting C’s, and this is a C, no need to worry.

To put this as harshly as I’ve sometimes felt it: If it’s a teacher’s job to sort kids into levels, grades make sense. If a teacher is meant to be a gatekeeper restricting access to future opportunities, ensuring a scarcity of qualified applicants for those opportunities, then grades make sense.

But if a teacher’s job involves paying attention to learners, understanding them, and working with them to help them grow, then grades aren’t worth much, and can actually get in the way.

Think about what freedom from grading meant for me and my students, as we worked together:

Freed from grading, I could put much of my energy into assessing what each child needed in order to make the best possible progress. I took lots of notes, and reviewed them less often than I thought I should, but often enough to keep my concerns and hopes for each student fresh.

Freed from grading, I could put much of my energy into assessing what each child needed in order to make the best possible progress. I took lots of notes, and reviewed them less often than I thought I should, but often enough to keep my concerns and hopes for each student fresh.

- We could make frequent and thoughtful use of student self-assessment. That’s awkward to incorporate into a grading system, but really important in helping students move forward.

Written quickly on the back of a math quiz, this is part of a student’s routine reflection on test-taking strategies and skills, with

Written quickly on the back of a math quiz, this is part of a student’s routine reflection on test-taking strategies and skills, with  my response.

my response.

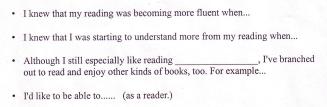

Here are some of the sentence starters for a reading journal self-assessment, leading up to a portfolio conference.

- My students and I weren’t in the more-or-less adversarial relationship that grading so easily encourages. Kids t

ended to be fully invested in the goals we had set together. So I got to hear them say things like this: “Something in me just rushes right through instructions, because I want to get started on the answers. So I’m trying to build the habit of stopping myself and reading the instructions again.” Or: “Now I can really understand what I’m reading, I get involved in what’s happening, and hate it when you say that reading time is over.” These are kids realizing what they need–habits of rechecking, reachable books–and figuring out that they can provide that for themselves.

ended to be fully invested in the goals we had set together. So I got to hear them say things like this: “Something in me just rushes right through instructions, because I want to get started on the answers. So I’m trying to build the habit of stopping myself and reading the instructions again.” Or: “Now I can really understand what I’m reading, I get involved in what’s happening, and hate it when you say that reading time is over.” These are kids realizing what they need–habits of rechecking, reachable books–and figuring out that they can provide that for themselves.

- Freed from grading that would imply class standing, we didn’t have to worry about an “even playing field.” I could help kids make individual choices of topics and materials comfortable enough to encourage confidence, interesting enough to inspire excitement, and challenging enough to nurture flexibility and pride. Like our physical education teacher, I aimed for “challenge by choice”–and I found that well-supported students motivated by genuine interest almost always aimed high.

There had been a rage for home-made marble chutes, in a run of rainy-day recesses. This student worked on his own to explore a new idea, incorporating a toy vortex.

There had been a rage for home-made marble chutes, in a run of rainy-day recesses. This student worked on his own to explore a new idea, incorporating a toy vortex.

At a professional conference, another teacher asked me, “But why do kids work, if there’s no grade as a reward?” I didn’t actually burst into tears, but I felt some despair. We are in real trouble when teachers themselves have been conditioned to forget the intrinsic rewards of learning, the joy of feeling powerful as a learner, the genuine appetite kids bring to t heir mutual effort to understand the world.

heir mutual effort to understand the world.

What about my own reward? Immeasurable. My students grew like weeds, not just physically but intellectually. They bloomed! That was the real delight, for me, in teaching at a school that disavowed grades: I got to watch kids learning like mad, bright-eyed and working tirelessly, full of the meanings in their learning and full of themselves, taking off and flying for their own reasons.

I wouldn’t trade that for nothin’. (Nada. Zip.)

I could not fit this topic into anything resembling my 1000 word target. So I’ve saved some aspects for another post: the relationship between grading (or not) and group work; ditto the development of class community. Also: in the absence of grading, kinds of feedback students could come to expect–and my continuing fascination with learning that happened in odd little corners (like rainy-day recess) where feedback wasn’t a factor.

When I did call time, students counted words, including any words crossed out. (Those crossed out words got written first, so they represented part of the writer’s output.) Nobody was allowed to marvel publicly about how many or how few words they’d written. They were meant to compare not with each other, but with themselves, day by day, page by page in their notebooks.

When I did call time, students counted words, including any words crossed out. (Those crossed out words got written first, so they represented part of the writer’s output.) Nobody was allowed to marvel publicly about how many or how few words they’d written. They were meant to compare not with each other, but with themselves, day by day, page by page in their notebooks.