#1 I’m beginning this post the way I wanted to end the previous one, with photos of kids reading, in the various positions and conditions my students adopted for silent reading time. (I finally found photographs, and got permissions.)

#1 I’m beginning this post the way I wanted to end the previous one, with photos of kids reading, in the various positions and conditions my students adopted for silent reading time. (I finally found photographs, and got permissions.)

Some sat on the floor leaning against the wall. Some sat on the big rug in the meeting area, often snuggled up next to each other like puppies.

Some sat at their table places, books on the table, heads ben t over, sometimes inside a curtain of long hair.

t over, sometimes inside a curtain of long hair.

(The girl in the background is going through a book stack, as in A Stack of Five.)

Some liked to hide in what kids called “the cave”, a little passage formed by the non-fiction bookshelves, with a rug on the floor, and with less visual or sound distraction than anywhere else in the room–which made another reason, besides privacy, to choose it.

One year I learned that I had to check that corner carefully if the fire alarm went off during reading time. A particular child remained cave-bound, reading straight through the horrific racket of the alarm. To my other overlapping mental categories of readers, I added, “children who could probably keep reading through an earthquake.”

#2 Intense mental adventures are happening in almost complete silence. I move around the room taking notes, but rarely interrupting. Conferences, one-on-one chats with an assessment often included, I try to do in the cubby area, outside the room.

The intensity of that quiet, a kind of sacredness, comes back to me as a I watch my grandson sleep, sense when he is dreaming, wonder what is happening in his dream.

#3 Reading is not sleeping, not dreaming, but reading fiction can be like dreaming someone else’s dream, so in a class of 15 there could be 30 minds dreaming, either creating or recreating stories: 15 students and 15 authors.

Often, though, there were local rages for particular authors. Several kids, recommending books for each other, might all be reading various titles by Nancy Farmer or Gary Paulsen, say. That could throw off my math.

Sometimes I imagined thought balloons above kids’ heads, full of the words they were reading, jostling with each other in the air space of the room; words perhaps moving from bubble to bubble, the way people can move from painting to painting in Harry Potter. The way enthusiasms can move through a reading community.

#4 When I first started teaching this age level, watching whole rooms full of kids reading, I was startled by how much I could tell about them as readers, just by watching their reading behavior, without even hearing them read.

Kids with strong reading skills, who nevertheless had to struggle to maintain focus / kids who were thrillingly a little drunk with the glory of new-found reading fluency / kids who were just too tired to read without falling asleep / kids for whom reading offered a sanctuary they might kill to protect / kids who began book after book but could never manage to finish one / kids who strongly preferred certain kinds of books / kids who could not read funny books without at least shaking slightly, or more likely poking a neighbor. All of that showed, with no need for assessments.

#5 I also discovered that assessments could be very useful. I used the Burns & Roe Informal Reading Inventory, a fairly standard assessment tool to which I had been introduced in graduate school. It gave me lists of words to hand a child, in order to check for ability to decode words without context clues. Then the child would read a passage, and answer the comprehension questions provided.

On my own, I requested a free retelling, which teased out slightly different aspects of a student’s comprehension. Finally, if we had time, I often asked for kids’ reactions, things the passage made them think about or wonder.

Depending on the child, I sometimes shared the results, and we talked over whatever they seemed to show. I wanted to get the kids’ own insights into their experience and history as readers.

An assessment of this sort is often used primarily to get a sense of the grade level at which a child is reading. More than that, I valued the way this series of activities gave me a sense of a child’s approach to reading.

Does the reader seem confident and engaged? Will she stop and deconstruct and parse out unfamiliar multisyllabic words, and use other clues besides the word itself, when those are available? Is he self-monitoring, or is he willing to tolerate and ignore meaningless readings? Is she finding a balance between inferring things the author never intended, and failing to make any inferences at all? Does he start out strong but wear out, or start out faltering and warm up? Does she read aloud flawlessly but then have no memory of what she read? Is he one of those slow and patient readers with lots of miscues, who nonetheless gives an inspired free retelling, and then answers every comprehension question perfectly?

Above all, is she comfortable enough to laugh out loud at my all-time favorite reading assessment line, about the ratio of sheep to humans in New Zealand? (18 to 1.)

Jokes aside, it’s how a child is reading, the kinds of energy a student brings to reading, that can tell us how to help that child move forward. We need to know what strengths can be the seeds for new growth, and we need that especially if there are also weaknesses. The same assessment tool I was taught to use in graduate school, with its capacity for pigeonholing, nonetheless turned out to be a great way to find out what I wanted to know: how a child’s intelligence was meeting the world of print, and what I could do to cheer and help.

#6 There are some important lessons to learn about reading, it’s true, and some of them can be taught in a whole class setting. For a while we received a classroom set of Boston Globes every Monday. (We were sad when their distribution arrangements no longer worked for us.) One day, we would read the bridge column–easily decoded words, all of them, that conveyed almost exactly nothing to a person without the right background knowledge.

This was a great way to encourage students to think about the difference between decoding and comprehending, and then go beyond that and think about the dimension of remembering. It’s hard to remember something that is gobbledygook in the first place–even if all the words are words you know. Remembering requires understanding, and understanding requires not just decoding–turning symbols into sounds–but thinking.

Definitely there’s a place for teaching reading skills. But…

It’s even more important to talk about the meanings in a piece of reading, and what the author has done to let them bloom. It’s important to write about reading, to use the discovery process of writing as a way of opening out the experience of reading, and sharing it with others. But…

None of those other peripheral activities should ever be allowed to displace actual time for reading, because actual time for reading is what most builds readers.

All that other stuff is what you do whenever you have enough time in the schedule. Reading itself has to happen no matter what.

#7 “It’s part of your religion,” a kid once said. She felt the same way, and probably had some truth on her side.

#7 “It’s part of your religion,” a kid once said. She felt the same way, and probably had some truth on her side.

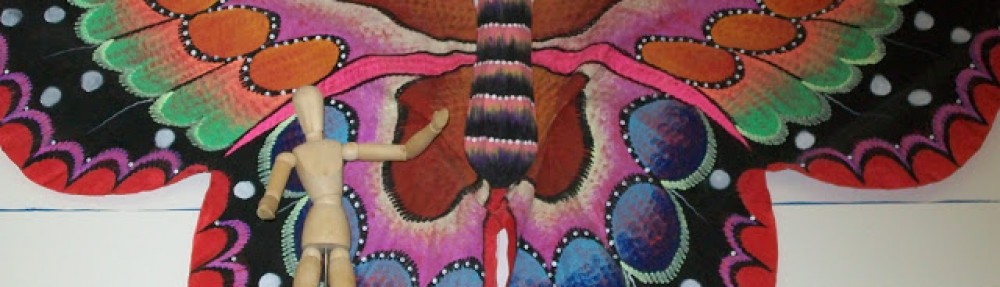

I imagine the same feeling in whoever made this little statuette, which I found on wikimedia commons, with no other attribution besides the name Pierre. Thank you, whoever offered this for us to find and remember!