Today I’m thankful for all my fellow word-lovers, past and present.

I’m thankful for my grandmother, who chatted with everyone she met, and picked up other people’s conversational expressions the way a dog picks up burrs. She kept and passed on treats like enough blue sky for a Dutchman’s britches and one pickle short of a quart. Listening to my mother and my grandmother talk together–with a what in thunder is he celebrating? here, and a heels-over-teakettle there–marked me for life, in the best possible way.

Once again, I’m thankful for George Batchelder, brilliant junior high English teacher, the one who gave us whole class periods for the Times crossword puzzle. He also asked us to list, on a page in our notebooks, plausible but nonexistent words: words with English prefixes and suffixes and blends, that were nonetheless fake, of our own manufacture: beautaceous, recrunk, preventicate, loombipuddle.

I’m thankful for a host of word-crazy students, including Andrew Cozzens, who often leaned over at dismissal to confide his word of the day. Even after he had left my school, he wrote emails telling me wonderful words he had recently discovered, such as loquacious.

I’m grateful for the poets of Every Other Thursday, whose recent poems have included the words moonbeamed, canted, phlegmatic, and loris, and the phrase crammed and nuzzling.

I’m everlastingly thankful for Alex Brown, and his children (who are also my children), and for our tendency, when together, to lapse into the synonym game without warning. Why stop with playful, when you can keep right on with lively, exuberant, high-spirited, festive and frolicsome?

That leads me (inexorably, but also gleefully) to word games. Today I offer just a few, in honor of long car trips to and fro, and in tenderness toward family relationships more amenable to word games than to talk about affairs either local or international.

Warning: there may be a sequel, down the road. In my family, word games were not scarce as hen’s teeth; we were two-thirds wealthy with them. (What?) And then I went on to invent some.

First, my grandmother’s (and mother’s) special rules for Scrabble.

- You may let a word edge over the boundary of the playing grid, by just one letter, any time you need to, in order to play a particularly satisfying word.

- If you have the right letter to replace a blank, you may do so, and take possession of the blank, at any time; this doesn’t count as a turn. (My cousin’s wife Terry, during one particularly hilarious game, replaced a blank with a blank, but I can’t remember why, only the way we were reduced to mirthful tears.)

- At the end of the game, everyone collaborates in an effort to place every last orphan letter on the board, in genuine legal words.

My mother, at 86, still won’t play Scrabble scored, because she wins so reliably that her opponents become discouraged (down-at-the-mouth, or even mad as a wet hen.) Once in a while, we’ll calculate the point value of a word just because it’s so delicious.

All my successive families have played the geography game in the car. My class used to play it when lining up for gym or dismissal.

- The first player names a place: a town, a country, a street, a river, a mountain–anything that could be on an ordinary map. Let’s say Merrimack River.

- The second player ignores parts of the name like River, focuses on the last letter, and comes up with a place name that begins with that letter. Given a K, the average person will say Kansas, but you can be playful–that’s the point, right?–and say Kalamazoo. I always try to, unless someone else has used it already in that game.

- Small children may name a place somebody else has already used, if they need to, and anyone may have help with the spelling of tricky place names with ph making the f sound, like Phoenix, or endings that sound like ee but are actually spelled with a y. Etc. Our language, including our geographic language, is full of these opportunities, but adults should go easy on the pedanticism. (No, you won’t find it. It’s in the category of plausible but manufactured.)

- You’ll want a good supply of place names that start with y, such as Ypsilanti.

- Do not be alarmed if your game drifts into the dreaded A-swamp: America / Australia / Andalusia / Africa… My class once made it through the entire line (becoming slightly late for dismissal in the process) using place names that begin and end with A. Like many hardships, the A-swamp arose there in our geography to test your indomitable spirit.

- In the days of smart phones, it’s easy to resolve arguments about spelling. In my family of origin, I was definitely not the final authority, having the spelling memory of a flea, or maybe a rock.

Speaking of spell-checkers, you can play a solitaire word game by typing in the names of your friends and seeing what the spell-checker makes of them. Or follow the eight-year-old Colby Brown’s example: randomly type a paragraph entirely in gibberish; then let the spell-checker do its best; then write an actual paragraph around whatever words the spell-checker has found.

Last, for now, here’s a game that requires either a dictionary or, if there are no dictionaries available, a referee. It’s called the Syllable Game, and this one I invented.

- We played this game many times beginning with the word Touchstone, the name of our school. Compound words generally work well, but the rules just require words of at least two syllables to start, and for every turn. In fact, you’re better off beginning with a word of three or four syllables. In class, this was often a word central to our current study. So, for example, transportation, or, for the purposes of the game, trans / por / ta / tion.

- The second player comes up with a word that preserves one of the syllables of the first word. This is where you need the dictionary, to check the official syllabication of the word, which will often contradict your first impression. (On the other hand, there is nothing like a car full of people carefully enunciating the word metamorphosis to judge its syllabication. Just designate a syllabication referee as well as a driver, and you’ll be fine.)

- In class, students were absolutely required to use a dictionary, which gave them great practice, exposed them to related words, and could lead to all sorts of pleasant detours.

- The pronunciation doesn’t have to be preserved, but the spelling has to be preserved exactly. So trans / late or por / tion or im / por / tant could all work as second turns, but port / man / teau or tran / scribe could not, because the por has been changed to port, and the trans has been changed to tran.

- Let’s say that the second player decides on trans / at / lan / tic. In a two-player game, the first player now jumps forward from that word, with all sorts of lovely possibilities: lan / guage or fan / tas / tic or at / ten / tion. Etc.

- The syllable you’re preserving can show up anywhere in the new word, jumping from second syllable to first, or third to first–so long as it’s the exact same syllable spelled the same way.

Assigning this as homework, I asked students to play with a parent or older sibling, and to record the whole ladder of turns, showing syllable breaks. Parents notoriously resisted using a dictionary, but came up with wonderful words.

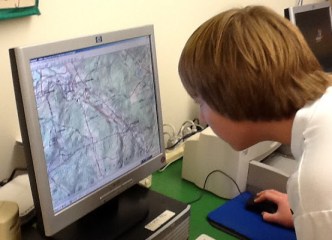

Finally, for whole class play, to help the game move faster, I invented a variation called The Syllable Web Game, which we played on the spare white board at the front of the room. Any syllable on the board was available to any player, even if it had already been re-used. (In the illustration, you can see how the ce from cement was reused in celesta, and then in celestial and cerulean and something I can’t read in the photograph.)

Finally, for whole class play, to help the game move faster, I invented a variation called The Syllable Web Game, which we played on the spare white board at the front of the room. Any syllable on the board was available to any player, even if it had already been re-used. (In the illustration, you can see how the ce from cement was reused in celesta, and then in celestial and cerulean and something I can’t read in the photograph.)

Usually we played this game during morning sketching time; sometimes also writing time and silent reading time. Players showed the syllabication and initialed their words, and then explained their meanings in the class debrief.

So now I bow, gratefully, to all the sources and innovators and playful practitioners of the language we share. It’s a very full room, and you’re all in it!

When I did call time, students counted words, including any words crossed out. (Those crossed out words got written first, so they represented part of the writer’s output.) Nobody was allowed to marvel publicly about how many or how few words they’d written. They were meant to compare not with each other, but with themselves, day by day, page by page in their notebooks.

When I did call time, students counted words, including any words crossed out. (Those crossed out words got written first, so they represented part of the writer’s output.) Nobody was allowed to marvel publicly about how many or how few words they’d written. They were meant to compare not with each other, but with themselves, day by day, page by page in their notebooks.