My father, 93 this year, barely speaks now. During the three days my sisters and I recently spent with him, he said little more than yes or no. Even for that he mostly nodded or shook his head.

The exceptions touched us deeply. When our father’s wife asked me to play their small organ, and we three daughters sang together, our father joined in for parts of “Dwelling in Beulah Land,” smiling broadly.

Before every meal, as we held hands around the table, our stepmother prompted our father to say grace. Sometimes he used words we’d heard throughout our childhood (until he and our mom separated and then divorced, and we saw him much less often.) Sometimes he used different words to request the same blessings, ‟living kindly in each others’ lives,” where the original grace asked that we be kept ‟mindful of the needs of others.”

Mostly, though, he listened to us. Sometimes he raised his head at a name, or to watch when one of us grew animated telling a story.

Through our childhood, and for many years after, our father was the most powerful talker we knew. A church deacon who sometimes filled in for the minister on Sunday, he helped to broker peace in a fractured congregation more than once. He sat on the school board in our town, helped build support for a new school, became a leader in his professional organization.

Through our childhood, and for many years after, our father was the most powerful talker we knew. A church deacon who sometimes filled in for the minister on Sunday, he helped to broker peace in a fractured congregation more than once. He sat on the school board in our town, helped build support for a new school, became a leader in his professional organization.

Later on, farm boy turned Green Revolution advocate and diplomat, he spoke persuasively to ministers of agriculture and heads of state all over the world.

We were immensely proud of him, and lucky ever to get a word in edgewise. In fact, the last five years we’ve been glad to have him dominate the conversation less, glad to have him listen more effectively and more appreciatively.

Near total silence felt different, awkward, heart-breaking. That talented, challenging, proud man sat at his dining table, folding a paper napkin along the diagonal and then throwing it into the waste basket. Then he started with another, and folded that one in half the other way, midpoint to midpoint, and then half again. He lined up his knife with the pattern of the tablecloth. He adjusted the position of a box of tissues, making it align precisely with the table’s corner. Looking at a stack of photographs, he positioned a smaller photo under the lower border of a larger one. Then he picked up another napkin and used it to measure the place mat, putting down a pointed finger to hold his place. All in silence.

Near total silence felt different, awkward, heart-breaking. That talented, challenging, proud man sat at his dining table, folding a paper napkin along the diagonal and then throwing it into the waste basket. Then he started with another, and folded that one in half the other way, midpoint to midpoint, and then half again. He lined up his knife with the pattern of the tablecloth. He adjusted the position of a box of tissues, making it align precisely with the table’s corner. Looking at a stack of photographs, he positioned a smaller photo under the lower border of a larger one. Then he picked up another napkin and used it to measure the place mat, putting down a pointed finger to hold his place. All in silence.

Without meaning to, I watched my father through a math teacher’s eyes. I thought, ‟He’s practicing spatial reasoning.” Practicing, doing the same thing again and again, to do it well.

I thought back. Our father’s professional and community roles depended heavily on his verbal persuasiveness, but strong kinesthetic and spatial intelligence has also shaped his life. Before I was born, he played basketball, and sometimes refereed. (Years later, reading John McPhee helped me appreciate the way a really good basketball player knows where every other player is, and where the ball is, moment by moment.) All of us had watched our father build boats, plan and create gardens, play pool, dance.

As I watched him now, adjusting objects edge to edge, experimenting with fit, I thought about pattern blocks, math manipulatives beloved by many of my students, which they used occasionally in math, and often during rainy-day recess.

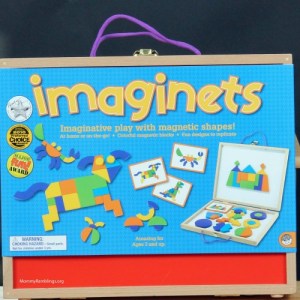

Where could we get some? On an errand at a nearby mall, my sisters and I saw a toy store. No pattern blocks, but we found something called Imaginets, from MindWare. Small flat wooden shapes painted in five brilliant colors, with magnets on the back, filled a wooden suitcase lined with shiny white magnetic surfaces.

Where could we get some? On an errand at a nearby mall, my sisters and I saw a toy store. No pattern blocks, but we found something called Imaginets, from MindWare. Small flat wooden shapes painted in five brilliant colors, with magnets on the back, filled a wooden suitcase lined with shiny white magnetic surfaces.

The set offered cards with designs to reproduce. By unanimous consent, we hid those right away, sensing in them an invitation to fail. That afternoon we just took out the box, and opened it on the table where the four of us sat together. After some fuss opening the plastic packages of shapes, one daughter set a purple rectangle in the middle of the white space. Another added to that shape a blue semicircle, lining them up the way our father had been lining up place mats. The third daughter added a green shape that became one of my favorites, an irregular pentagon.

We all held our breath. Would our wordless father join in?

With the exquisite care of a ferry pilot approaching a dock, he steered the piece he’d chosen into the position he had chosen for it. When we oooohed and ahhhhed with appreciation, he beamed.

Gradually, as we kept playing, our father joined in with increasing confidence. He had his own sense of fit and appropriateness, in this completely non-competitive, non-verbal, intuitive game we were all inventing together. Until recently, we realized, he might not have been able to do anything this loose, this unconcerned with winning. Here he is, to the right, with one of our completed designs, which fulfilled our goal of using every piece in the set.

Gradually, as we kept playing, our father joined in with increasing confidence. He had his own sense of fit and appropriateness, in this completely non-competitive, non-verbal, intuitive game we were all inventing together. Until recently, we realized, he might not have been able to do anything this loose, this unconcerned with winning. Here he is, to the right, with one of our completed designs, which fulfilled our goal of using every piece in the set.

When we started letting the curved shapes be tangent instead of fitting closely, he went along for the ride. We grew more and more relaxed about taking turns, particularly after our father added seven shapes one after another, in a run of brilliant yellow, and looked up, pleased with his own sophistication.

I turned away, not wanting him to see tears. Transcending everything that made it hard for us to communicate, we were having a kind of conversation. A man in hand-to-hand combat with dementia, losing one capacity after another, our father was learning.

I wrote the first draft of this post riding north again on the train (a happy little link to the previous post about riding trains with my students.) As I watched the eastern seaboard slide by, creek by creek and cove by cove, I kept mulling it over. My daughter, by phone, suggested the string of words I might use for an online search about spatial / kinesthetic / sensory experience for the elderly. (And I’d welcome leads from any of my readers.)

Already, I can say this much. Unlike the students I observed and fell in love with and learned to support both verbally and non-verbally, my father does not have years of growing and learning ahead. He’s in his last chapter, no matter what right games we find. But he, too, needs and can savor the experience of learning. He is still one of us, a human, seriously playing.

Already, I can say this much. Unlike the students I observed and fell in love with and learned to support both verbally and non-verbally, my father does not have years of growing and learning ahead. He’s in his last chapter, no matter what right games we find. But he, too, needs and can savor the experience of learning. He is still one of us, a human, seriously playing.

In today’s email, I found a photograph our stepmother had taken, shown above, in which our father builds designs with the Imaginets on his own.

This photograph, taken by one of my sisters, captures the image in my heart. I wanted to focus this post on my father, but I come to the end of it needing to thank not only my father but also my funny, creative, wise sisters, and my brave and patient stepmother–all the hands in this photograph. Also our mother, blessing this visit from her distance, and our families, giving whatever they can to the dispersed village we are together.

This photograph, taken by one of my sisters, captures the image in my heart. I wanted to focus this post on my father, but I come to the end of it needing to thank not only my father but also my funny, creative, wise sisters, and my brave and patient stepmother–all the hands in this photograph. Also our mother, blessing this visit from her distance, and our families, giving whatever they can to the dispersed village we are together.

I think also of my students, from whom I learned so much that is still with me, about all the ways to be alive and aware–and learning–in this world.

Polly, this is such a moving post that I also needed to wipe the tears away. The withdrawal you speak of in your father is poignant, but the way you connect his movements with spatial reasoning — stunning. Thank you, thank you.

I found myself wishing that I had my sisters at my side, in complicated moments like those, much more often. So grateful for the thoughts and momentum we could have together. Like the collegial side of teaching, which I miss.

I think part of the essence of loving our elders well is meeting them where they are — not as how we remember them, or as we want them still to be, but as who they are in the present — and seeing what there is rather than what there is not. And then we have to build, connect, from there. With luck we can find a new kind of language.

I find myself imagining a world in which the dialogue about elder care focused significantly on tools like Imaginets — giving caregivers and families not naturally inclined to think about changing abilities in that way a head start in navigating evolving terrain.

…and it seems as if that perspective and practice of discernment is growing, yes? From various indications online, on the radio, etc.

slowly