Early in my graduate education, I took a Lesley University summer school course about teaching mathematics, with a genuine, fresh-from-the-trenches middle school math teacher, Lloyd Beckett. Authentically–and contagiously–he had come to believe in the power of math conversation, and in the rich gifts students with different approaches could offer each other.

Lloyd’s course woke me up as a math teacher and as a mathematician. For years I had assumed that my relatively decent math grades rested completely on my ability to memorize. As it stood, that was largely true. When I did particularly well on one of the New York State Regents exams, my teacher, Augustus Askin, whom I adored, looked at me and said, “How did you do that?” Although I don’t think he suspected me of cheating, he had seen the puzzled look I often wore in math class.

Memorizing was okay for the test, but the effects never lasted very long. Real understanding, for me, required experiences that math class rarely offered–that I couldn’t even imagine math class offering.

On the other hand, in secret, generating that puzzled look, I’d spent years figuring out my own approaches. I could hold onto math concepts, and work with them comfortably, if I experienced them pictorially or concretely, or told stories about them. This was in a time, though, before math manipulatives, at least in my country schools, and before the wonderful math videos I was able to use with my own students, decades later.

There were exceptions. A little girl for whom I babysat had one of those balance toys with numbers weighted to add or subtract properly. If you hung a 5 and a 2 on one side, and a 7 on the other, the balance came to rest with the pointer in the right place to mean yes.

Here’s a sample of a similar balance still on sale.

Other, purer versions make more sense for older kids, but I spent a lot of time playing with that balance, savoring it. It was what I needed.

I’m also stubborn, and I hated subtracting. All on my own, with no support from the rote-memory approach in school, I had figured out a way of subtracting by adding, doing a sort of mental algebra: what plus 5 will equal 7? Or what plus 9 will equal 17?

In my earnest little heart, though, I suspected that I was cheating. I thought I was making up for not being good at math.

Years later, when I spoke with parents at math curriculum nights, I sometimes called myself a “born-again mathematician.” Teaching math with new math tools and toys and approaches, and with new respect for many kinds of math minds, I found that I loved math, respected my own math learning style, and got a huge kick out of helping all sorts of kids come to understand new math ideas and feel new math power.

That marked me for life, evidently. In my current pause from teaching, any time a math idea sails into my day, I grin and go with it. So, for any of you who feel math deprived, just through the holiday, or in your everyday life, I offer a few math games.

The first two aren’t really games, just reflexes.

When I tear myself out of whatever book I’m reading, I play with the page number as I walk away. 139. Hmmmm: is that prime? It might be, since none of the proper factors of 100 overlap with the factors of 39…

When someone in our family has a birthday, I figure out the prime factorization of the new age. My father recently turned 92. Let’s see: 2 x 46, or 2 x 2 x 23. Suddenly I feel, inside the 92, an 80 (4×20) and a 12 (4×3). Oooh, cool.

Last year, my daughter’s children were both prime, 3 and 7. As of a few days ago, they are both powers of 2, having turned 4 and 8 (or 2×2, and 2x2x2.) Abe is now twice as old as Julia, and that will never happen again.

What official-sounding thing can we call this? A mathematical storytelling impulse? It works for me.

But other things can work, too. I’ll never forget the day my kids and I stopped by Kate Keller’s house for a quick visit, and learned now to play Set, from watching her play it–because she refused to tell us the rules. Obsessed, we came home and made our own version out of file cards. Later on, watching my students play Set was like giving them a diagnostic test. Some kids were quicksilver zippy at Set, and slow at everything else that happened in class. Some kids were slow, as I am, but warmed up as they went along. Clues, clues. And hilarious fun: in math choice times, I had to limit the number of kids who could play Set together, because that corner would get so loud.

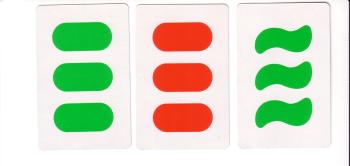

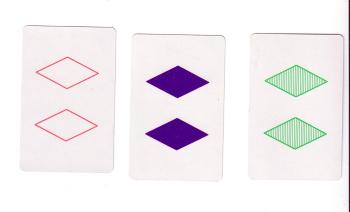

This is not a Set:

But this is:

…and this is a particularly delicious Set:

…and this is a particularly delicious Set:

To learn more, you could track down Kate Keller, my all-time-most-important math mentor, who has more fun with math than anyone else I know. She also perceives and nurtures students’ math individuality with something I can only call math compassion, a power almost magical.

To learn more, you could track down Kate Keller, my all-time-most-important math mentor, who has more fun with math than anyone else I know. She also perceives and nurtures students’ math individuality with something I can only call math compassion, a power almost magical.

Or follow this link to the Set Wikipedia entry; it’s fascinating! There are ways to play Set online now, too–a discovery that could sharply curtail my future productivity.

Finally, Lloyd’s Game. Of course, he probably called it something else. I’ve sometimes imagined Lloyd just up and quitting when one of his best whole class math games no longer worked. 1999 was a great year for this game, but the very next year, 2000, was hopeless.

In Lloyd’s Game, you have access only to the digits in the Gregorian calendar’s count for a given year. You combine those with math symbols (no quota on those) to create expressions equaling the numbers from 1 to 100. You must use all four digits in each expression, and you may not use two-digit numbers made from combinations of digits (although I remember resorting to that a few times when nothing else worked.)

Generally, in class, we used the new year’s digits to create the numbers of the days in January, catching up with a burst of activity when we came back from the holiday break or weekends, but mostly targeting each number as it came up, day by day. We used the basic operation symbols, + — × and ÷, along with parentheses, the fraction bar, the square root symbol, and the exclamation point meaning factorial. We were allowed to use a number as an exponent, so 1 to the 9th power was an excellent way to dispose of a superfluous 9.

Here are two examples, using 1989:

The best fun came in class, as we compared multiple ways of arriving at the same target number. Gradually, as January progressed, we watched and cheered breakthroughs for kids who had initially feared the game’s challenge.

Here are three ways of making 5, from one of the posters we hung up around the room, again from working with 1989:

After 2000, a flop for obvious reasons, we sometimes used the year in which the largest number of kids in the class had been born. Sometimes I chose numbers relating to our themes: the year Charles Darwin was born, the year the Blackstone Canal was first opened, etc.

Try it out, alone or with some pals. You can use the birth year of your favorite politician—they’re all still creations of that wonderful (for this purpose) century past.

In any case, life is short. Go ahead and feel human. Play with math while you can!